2026 – Will the Munich Security Conference be without expectations?

Maritime Security Forum

The 2026 Munich Security Conference is taking place in a climate marked by caution, uncertainty and strategic recalibration. Beyond the official statements by European and American leaders on the continuity of transatlantic dialogue, real expectations for concrete results are limited. This discrepancy between public discourse and informal assessments reflects a mood specific to the current moment: not one of open rupture, but of latent mistrust and gradual adjustment of positions.

Whatever European officials in Munich said about their expectations for the current round of transatlantic dialogue on security issues, the answer was clear, expressed in just three words: “not much”.

For Europeans, major differences remain that need to be resolved urgently before things can possibly return to normal. Discontent continues, fuelled by the Greenland incident, and confidence in the United States has eroded in the future of transatlantic cooperation. Defying recent calls by NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte and his predecessor Anders Fogh Rasmussen to maintain the nearly eight-decade-old alliance, Europe’s frustrations with US President Donald Trump’s brinkmanship tactics are still alive. Concerns about possible new surprises – whether we are talking about interventions in the style of US Vice President JD Vance at the MSC in 2025, or phrases such as “wiping out civilisation” from the US National Security Strategy – are deeply rooted.

Discussions about the need for Europe to have a Plan B to guarantee its own security, independent of the United States, are beginning to emerge in the run-up to the MSC meetings. Calls for European sovereignty will resound in numerous sessions. Although more nuanced arguments will rightly emphasise the importance of the transatlantic relationship, the focus will shift to how Europe needs to adapt its defensive posture, taking into account the dynamic changes across the Atlantic – whether these take place within or outside the existing structures between the two sides.

The title of the MSC’s annual report, “Under Siege”, clearly illustrates why Europe seems to be becoming less and less relevant in the new geopolitical landscape. The continent seems stuck in the phase of diagnosing the problem, instead of moving forward with proposing solutions. Europe must begin to clearly outline what it expects from a transatlantic partnership that needs to be reconfigured and brought into a new balance. The MSC would be the ideal framework for initiating this process.

Is Europe in the midst of disintegration or does it have a vision for a new construction?

Ahead of the Munich Conference, one of the recurring questions in European strategic analysis circles concerns the direction in which the continent’s security project is heading. Beyond symbolic formulations, the dilemma is a structural one: is Europe going through a phase of strategic fragmentation or, on the contrary, is it undergoing a slow process of reconstruction, driven by external pressures and new geopolitical realities?

Looking at the big picture, we need to pause and separate the hype from the facts. To do this, we suggest reflecting on the positive, negative and dangerous aspects in the context of the meeting of transatlantic and world leaders in Munich – with a few ideas on how everyone could come out stronger. First, it is useful to examine the beneficial effects of Trump’s destabilising actions and pressures.

After a long period of reduced investment and political neglect, the US’s European partners are finally allocating increased funds to defence forces and military training, training together more often and taking their security responsibilities more seriously in the fourth year of Russia’s bloody war against Ukraine – against a backdrop of growing hybrid threats to the old continent. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte sparked debate when he told Europeans that without Trump’s contribution, none of this would have happened.

Secondly, economic shocks from China and the United States have forced Europe to realise more deeply – even if it has not yet implemented appropriate solutions – its deficits in technological innovation and entrepreneurship, the excessive burden of unhelpful regulations, and insufficient efforts to create a real union in the capital markets, defence and foreign policy.

Thirdly, we will analyse the Middle East, where the chances for lasting regional peace and prosperity, along with better economic and security connectivity, have rarely been greater. Iran, the destabilising actor in the region, has hardly ever been weaker. Both its defensive and offensive capabilities are diminished, its nuclear potential is seriously affected, its indirect representatives are neutralised, and its economy is facing difficulties, while internal discontent is smouldering. All these elements are positive.

Last but not least, despite the accumulation of geopolitical risks, global economic indicators performed remarkably well in 2025. International financial markets, including those in Europe and the United States, reached new highs, suggesting a partial decoupling between strategic risk perception and short-term economic dynamics. This discrepancy is, in turn, a relevant factor in assessing the overall stability of the international system.

The dominant theme of the conference: the transatlantic crisis of confidence

The 2026 edition of the Munich Security Conference is marked by a theme that recurs in most panels and speeches: the weakening of trust in transatlantic relations. The conference organisers described the preparation of this summit as a process characterised by heightened volatility and constant adjustments, in a context where unpredictability is no longer an anomaly but a constant feature of the current strategic environment.

Wolfgang Ischinger, who has long headed the MSC and is a lifetime member of the Atlantic Council’s board of directors, offered a blunt assessment ahead of this year’s session: “Transatlantic ties are, in my view, suffering from a serious lack of trust and credibility.”

When alliance partners cannot rely on each other’s intentions or actions, dangers arise in the dynamics of the relationship. Certain nations in Europe have already begun to take precautions against uncertain scenarios in which American assistance in the event of aggression could be delayed, subject to conditions, diminished or even non-existent. Such self-protection undermines the deterrent effect.

In this context, MSC 2026 is perceived less as a forum for major decisions and more as a space for assessment and recalibration. Discussions do not focus exclusively on identifying immediate solutions, but on managing an ongoing transition in which the transatlantic relationship remains functional but is subject to persistent structural tensions.

Two possible scenarios after Munich

There is a note of unease in Munich. Europe’s exaggerated reaction to President Trump’s actions risks squandering an extraordinary opportunity – the chance for a strengthened and profoundly improved Europe to shape, alongside its ally of the last eight decades, the United States, the next phase of the international order. The US is not seeking to demolish the existing order, but rather to reposition it, involving reduced costs for itself and transferring more tasks to its partners. Indeed, we must admit that the MSC report also highlights this hypothesis, drawing parallels with the period immediately following the Second World War.

The first scenario assumes that the European response to the actions and statements of the American administration will remain predominantly defensive and fragmented. In this hypothesis, the emphasis is on managing specific tensions and avoiding political escalation, to the detriment of formulating a coherent strategic vision. Such an approach risks diluting Europe’s opportunity to leverage external pressures as a factor for internal consolidation and redefining its role within the international order. From this perspective, adaptation would take place through reactive measures, not through in-depth strategic coordination.

The second scenario considers the possibility that current tensions could act as a catalyst for more structured and coherent European involvement in shaping the transatlantic relationship. In this scenario, a Europe that is more financially and operationally engaged could actively contribute to shaping the next stage of cooperation with the United States, within a framework in which responsibilities are redistributed and costs are shared more evenly. This development does not imply a renunciation of the existing architecture, but rather a gradual adjustment of the way it works.

In analysing these scenarios, it is relevant to note that the United States does not seem to be seeking a complete demolition of the post-war international order, but rather a repositioning that reflects changes in power and internal strategic priorities. This interpretation is also supported by the MSC’s annual report, which identifies parallels between the current moment and the period immediately following the Second World War, when the redefinition of responsibilities was accompanied by significant tensions and adjustments.

The MSC report notes: “A lifetime later, Acheson’s current successor, Marco Rubio, used similar language during his confirmation hearings, arguing that the US was ‘once again called upon to build a free world out of chaos’ because the existing system no longer served American interests and was being exploited by others.

Against this backdrop, the dilemma was summarised: “The essential questions we are seeking answers to this weekend are: Is the global order we have grown accustomed to doomed? Are we witnessing the decline of progress, or are we witnessing what [Joseph] Schumpeter called ‘creative disintegration’, a painful process that ultimately leads to something superior? Or are we witnessing destructive creation, giving rise to something that will lead to the end of all things?

It is difficult to imagine a more decisive turning point than the one that must decide between these two perfectly plausible premises. The stakes have never been higher than at the opening of this annual MSC summit.

Relief and a hint of irritation may have been the first emotions felt in European capitals after US President Donald Trump dropped the subject of Greenland in Davos. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte once again confirmed his talent as an unrivalled interlocutor for Trump, assisted by latent anxiety in the financial markets and a surprisingly united Europe that stood its ground. Rutte’s general plan with Trump, however vague in detail, seemed to prove right those who argued that Europe should “engage, not escalate” with the White House leader.

However, just one day after news of the Arctic agreement in the Alps, the mood among European decision-makers was changing, moving beyond mere relief. Although Trump had threatened to remember if he did not get what he wanted regarding Greenland, Europeans will remember this dispute even after Trump has left the scene. Few are celebrating the calming of the situation, given how pointless and ill-advised they consider this latest attempt to validate the Alliance’s solidarity and cohesion. And because they know that this is probably only a temporary postponement, certainly not the last transatlantic crisis to be expected from this American administration. The result is a quiet but firm decision to develop Europe’s ability to withstand pressure from the US in any anticipated scenarios generated by an American president perceived as unpredictable, if not unstable. As an indication of the impact of recent days and weeks, European Union (EU) leaders nevertheless gathered on Thursday for an extraordinary summit in Brussels, despite the de-escalation of the immediate issue.

Overall, the Greenland episode was not a major crisis in itself, but it served as a test of the resilience of the transatlantic relationship. The way it was handled highlights both the adaptability of existing mechanisms and their limitations in a context characterised by recurring political pressures and fragile strategic trust.

Tracking NATO defence investments. How are Alliance members contributing to the common defence effort?

One of the recurring themes of the 2026 edition of the Munich Security Conference is the evolution of NATO member states’ financial efforts and how these translate into concrete defence capabilities. In this context, recent data indicate a significant change from the trends of the previous decade, both in terms of expenditure levels and the diversification of criteria for assessing national contributions.

The Transatlantic Security Initiative, developed by the Atlantic Council, has launched an updated platform for real-time monitoring of NATO investments, with the aim of providing a more detailed picture of how each ally contributes to collective defence. This approach goes beyond the traditional assessment based solely on the percentage of GDP and includes indicators such as actual investments in equipment, infrastructure, personnel and support for Ukraine.

According to the latest available data, all NATO member states have exceeded the 2% of GDP threshold for defence spending set in 2014 at the Newport Summit. This development marks a symbolic moment for the Alliance, given the difficulties previously encountered in achieving this common goal. At the same time, it reflects the cumulative impact of geopolitical pressures and the deteriorating security environment in Europe’s eastern neighbourhood.

A comparative analysis of spending reveals significant differences between member states. Poland remains among the leaders in terms of the percentage of GDP allocated to defence, while other states have set different timetables for achieving the new targets. For the first time in NATO’s history, a European country – Norway – has surpassed the United States in per capita military spending, an indicator that highlights the gradual change in the contribution profile of European allies.

Standards are rising. At the NATO Summit in The Hague, allied leaders agreed on a new financial benchmark for defence spending: the target is now 5% of gross domestic product allocated to defence by 2035. This new commitment involves an allocation of 3.5% for strictly military operations and equipment (troops, weapons) and 1.5% for essential support elements, including vital infrastructure, cyber security and other measures to strengthen resilience.

The monitoring tool examines members’ defence spending patterns through metrics that go beyond the percentage of GDP – from actual amounts invested in armaments to support provided to Ukraine.

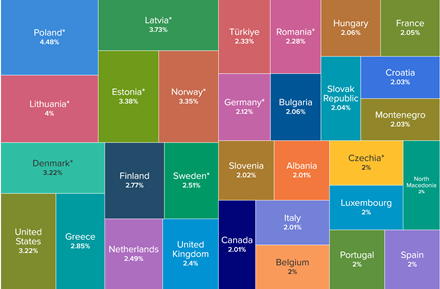

Proportion of GDP allocated to defence (2025 projection)

Against the backdrop of the introduction of the new spending benchmark, member nations are increasing their budgets to reach the 5% target. Poland remains the leader in terms of percentage of GDP allocated to defence, with a value of 4.48%. It should be noted that all allies have managed to exceed the previous 2% threshold – an issue that has been a source of tension within the Alliance over the past decade.

Source: NATO

Percentage of Gross Domestic Product allocated to defence, according to plans

All members of the alliance, with the exception of Spain, have committed to reaching the target of 5% of GDP for military spending by 2035. However, it is essential to understand the difference between the amount declared as an intention and the amount actually budgeted. This graph details the specific strategies for increasing defence funding communicated by the allied states.

| Albania | 2.5 | 2029 | Hungary | 2 | 2026 | Germany | 3.50 | 2029 | |||

| Belgium | 2.50 | 2034 | Iceland | 0 | Greece | 3.50 | 2036 | ||||

| Bulgaria | 3.50 | 2032 | Italy | 2 | 2028 | ||||||

| Canada | 2 | 2025 | Latvia | 5 | 2026 | Sweden | 3.50 | 2030 | |||

| Croatia | 3 | 2030 | Lithuania | 6 | 2030 | Turkey | 3.5 | 2026 | |||

| Czech Republic | 3 | 2030 | Luxembourg | 2 | 2026 | ||||||

| Denmark | 3+ | 2026 | Montenegro | 3 | 2027 | United Kingdom | 2.50 | 2027 | |||

| Estonia | 5.40 | 2029 | Netherlands | 2.20 | 2026 | United States | 3.3 | 2026 | |||

| Finland | 3 | 2029 | Slovak Republic | 2 | 2026 | ||||||

| France | 2.30 | 2027 | Slovenia | 3 | 2030 | ||||||

| Spain | 2.1 | 2026 | |||||||||

Military budget per capita (2025 projection)

The sharing of responsibilities is not limited to the share of military spending in gross domestic product. For the first time in the organisation’s history, another NATO member has exceeded the United States’ per capita financial contribution to defence. More specifically, Norway allocates approximately $723 per citizen in addition to the amount invested by the US for defence purposes.

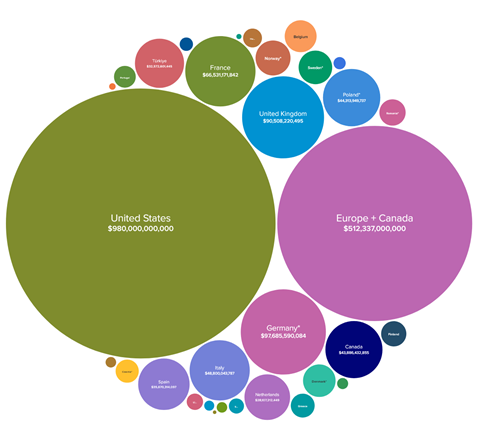

Total defence budget (2025)

In terms of total defence budget, the United States stands out as the clear leader — it allocates significantly more resources than all European allies and Canada combined. However, as the US is a major global power with worldwide interests and the ability to project its power far beyond Europe, its defence spending is not limited to the Euro-Atlantic area. Therefore, this apparent discrepancy does not fully reflect the complexity of the distribution of responsibilities within the NATO alliance.

Allocation of financial resources for defence by sector (2025 estimates) – Percentage of national defence budget for 2025

While the total amount allocated to defence is relevant information, how these funds are used is perhaps even more decisive. Some members of the alliance, such as Greece, have been criticised because including military pensions in total military expenditure increases the percentage of GDP devoted to defence without necessarily implying a direct increase in NATO’s operational potential. On the other hand, countries such as Denmark argue that their expenditure estimates do not reflect the significant personnel contributions they make to NATO missions, such as the operation in Afghanistan. To clarify this perspective, this graphic illustration shows the breakdown of defence budgets across different areas. These data highlight a common problem: allocations for infrastructure often lag behind other areas of military spending. This indicator is expected to become increasingly important as alliance members determine what types of commitments can be counted toward the 1.5% of defence spending reserved for military facilities. Political leaders are likely to direct investment towards infrastructure projects that serve both civilian and military purposes in order to boost defence spending.

| Country | Equipment | Personnel | Infrastructure | Other |

| Albania | 42.12 | 33.41 | 3.70 | 20.77 |

| Belgium | 14.54 | 32.44 | 3.73 | 49.29 |

| Bulgaria | 29.11 | 52.79 | 2.36 | 15.74 |

| Canada | 22.55 | 36.02 | 1.44 | 39.99 |

| Croatia | 29.87 | 54.31 | 1.31 | 14.51 |

| Czech Republic | 30.68 | 28.72 | 14.07 | 26.52 |

| Denmark | 18.93 | 1.07 | 34.39 | |

| Estonia | 25.83 | 22.64 | 8.04 | 43.50 |

| Finland | 45.97 | 17.97 | 0.18 | 35.88 |

| France | 31.03 | 38.22 | 3.83 | 26.92 |

| Germany | ||||

| Greece | 35.00 | 58.45 | 0 | 6.55 |

| Hungary | 44.95 | 28.20 | 5.75 | 21.09 |

| Italy | 25.68 | 42.85 | 1.90 | 29.57 |

| Latvia | 35.50 | 29.77 | 5.60 | 29.13 |

| Lithuania | 45.84 | 25.29 | 6.05 | 22.82 |

| Luxembourg | 53.51 | 11.73 | 7.05 | 27.71 |

| Montenegro | 34.27 | 44.40 | 6.64 | 14.69 |

| Netherlands | 26.05 | 30.57 | 3.09 | 40.28 |

| North Macedonia | 32.36 | 41.00 | 1.84 | |

| Norway | 31.44 | 20.45 | 4.71 | 43.41 |

| Poland | 54.44 | 26.75 | 3.76 | 15.05 |

| Portugal | 20 | |||

| Romania | 31.81 | 45.23 | 13.57 | 9.39 |

| Slovak Republic | 31.10 | 38.86 | 4.32 | 25.72 |

| Slovenia | 26.55 | 31.29 | 2.20 | 39.96 |

| Spain | 32.29 | 27.76 | 4.63 | 35.32 |

| Sweden | 35.83 | 14.45 | 0.40 | 49.33 |

| Turkey | 27.00 | 34.41 | 7.39 | 31.20 |

| United Kingdom | 35.96 | 29.25 | 2.80 | 31.99 |

| United States | 29.69 | 27.31 | 1.87 | 41.12 |

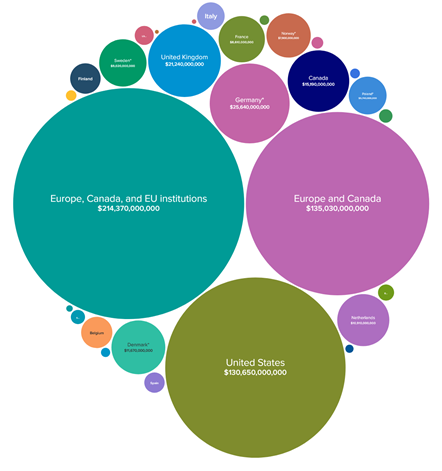

Total assistance provided to Ukraine separately (for 2025)

Trump frequently claims that the United States has provided Ukraine with considerably more military, humanitarian and financial support during the conflict; however, the total amount of individual contributions from European countries is close to that of the United States. If the contributions of individual European countries are added to the assistance provided by the European Union, the final result substantially exceeds US support for Ukraine — highlighting the commitment of European allies to security issues in their immediate neighbourhood.

Per capita assistance to Ukraine (2025)

When we look at per capita contributions, a number of European allied nations significantly exceed the United States in terms of financial support to Ukraine. Leading the pack are the Nordic and Eastern Flank nations, with Denmark at the top of the list. The statistics clearly show that the main financial burden of supporting Ukraine is already being borne by European partners.

Will the United States maintain its defence commitments despite the current tensions?

Despite the climate of uncertainty characterising transatlantic relations ahead of the 2026 MSC, most strategic assessments converge on the idea that the United States will continue to play a central role in the Euro-Atlantic security architecture. Prospective analyses by security and geopolitical experts indicate that Washington is expected to retain its dominant leadership status within NATO, even if the nature of this leadership is subject to adjustments.

In the so-called annual surveys on projections for the next decade, most geostrategy and forecasting specialists anticipate that the US will maintain its position as the “dominant leader within NATO” – but, at the same time, Europe is expected to take on a greater share of its own defence burden, pursuing strategic independence.

This perspective is linked to a gradual change in American expectations of its European allies. The emphasis is shifting from almost unilateral security guarantees to a more balanced sharing of responsibilities, in which Europe is called upon to strengthen its defence capabilities and strategic resilience. In this context, the maintenance of American commitments is not questioned in absolute terms, but is conditional on the ability of allies to contribute more consistently to collective security.

From Washington’s perspective, this approach reflects both domestic constraints and competing global priorities. Budgetary pressures, internal political polarisation and the need to manage multiple theatres of strategic interest simultaneously influence the way in which external commitments are calibrated. Europe remains an essential pillar of international security, but it is no longer the only area that demands American attention and resources.

In this context, frequent comparisons between the financial efforts of the United States and those of its European allies take on increased relevance. Although the total US defence budget significantly exceeds aggregate European contributions, these expenditures reflect a global strategic posture with extensive commitments outside the Euro-Atlantic space. This reality complicates the assessment of the fairness of burden sharing and fuels recurring debates on the criteria used to measure effective contributions.

For European actors, the uncertainty stems not so much from the possibility of a US withdrawal as from the variability of the conditions under which support might be provided. Scenarios under consideration include delays in response, political conditions, or prioritisation of other regions in situations of simultaneous crisis. These assessments do not indicate an imminent rupture, but they do influence the way in which European states plan their own defence capabilities and define their margin of strategic autonomy.

Overall, MSC 2026 is not anticipated to be a moment of definitive clarification on these issues. Rather, the conference provides a framework for dialogue in which ambiguities are acknowledged and managed, without being completely eliminated. Maintaining American commitments remains central to European security, but it is increasingly linked to the evolution of European allies’ contributions and strategic coherence.

China, Taiwan and the reconfiguration of American strategic priorities

In addition to European and Euro-Atlantic issues, the 2026 edition of the Munich Security Conference is paying increased attention to developments in the Indo-Pacific, particularly the relationship between China and Taiwan. Although this dynamic is unfolding at a geographical distance from Europe, its strategic implications are directly relevant to the transatlantic relationship, as it influences the global priorities of the United States and the distribution of security resources.

During events associated with the MSC, US officials emphasised the need to assess the global context in an integrated manner, avoiding fragmented approaches. In this regard, Congressman John Moolenaar, chair of the House Working Group on Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, drew attention to the risk that misperceptions about Taiwan could become geopolitical realities through accumulation and lack of coordinated response.

His statements highlight a constant concern for Washington: maintaining strategic balance in the Taiwan Strait without introducing additional red lines that could amplify tensions. In this context, support for Taiwan is presented not only as a matter of regional security, but as an essential element of American strategic credibility globally. The United States’ ability to honour its commitments in the Indo-Pacific is seen as an indicator of its reliability in other regions, including Europe.

At the same time, US officials acknowledge the existence of structural constraints related to the defence industrial base and the pace of military equipment deliveries. These limitations are relevant to European allies, as they suggest a strategic environment in which American resources must be prioritised among multiple theatres of operations. In this context, strengthening interdiction and deterrence capabilities in the Indo-Pacific may indirectly influence the level of attention and resources allocated to the Euro-Atlantic area.

From a European perspective, developments around Taiwan are relevant not only in terms of global security, but also in terms of economic and technological interdependencies. Taiwan plays a central role in global supply chains, and major destabilisation in the region would have significant effects on European economies, particularly in the technological and industrial sectors. This dimension adds an extra layer of complexity to debates on strategic priorities and the need for closer coordination between allies.

Overall, the China-Taiwan issue is addressed in the MSC 2026 as part of a broader strategic landscape in which the United States must simultaneously manage competition between major powers and commitments to allies. For Europe, this reality reinforces the importance of taking on a more consistent role in its own regional security, in a context where American attention is distributed globally.

Conclusions

The 2026 Munich Security Conference takes place in a context characterised by strategic uncertainty and the recalibration of international relations. Unlike previous editions, the focus is not on anticipating major decisions or launching new initiatives, but on assessing transformations already underway, both in the transatlantic relationship and globally.

The relationship between Europe and the United States remains functional, but is marked by an erosion of trust and increased political unpredictability. This dynamic does not indicate an imminent rupture, but it does influence the way European states assess their strategic dependencies and plan their security capabilities. In this sense, the Munich Conference is perceived as a space for dialogue and adjustment rather than a forum for definitive decisions.

The financial efforts of NATO member states reflect a significant change from the previous period, with widespread increases in defence budgets and a diversification of criteria for assessing contributions. At the same time, persistent differences in the structure of expenditure and the pace of achieving new targets highlight the challenges of coherence and coordination within the Alliance.

Assistance to Ukraine remains a central element of the European and transatlantic security agenda. Available data indicate substantial involvement by European states, both in absolute terms and per capita, underscoring Europe’s increasingly active role in managing security in its immediate neighbourhood.

At the same time, developments in the Indo-Pacific, particularly the relationship between China and Taiwan, indirectly influence the strategic priorities of the United States and the distribution of security resources. This reality adds an additional layer of complexity to the transatlantic relationship and reinforces the importance of increased security responsibility at the European level.

Overall, MSC 2026 is shaping up to be a conference of assessment and adaptation, in which the main actors recognise the current limitations and constraints, without formulating expectations for quick solutions or radical changes. The debates in Munich reflect a moment of transition in the international security architecture, in which continuity and adjustment coexist in a fragile balance.

Throughout the MSC, commentators will analyse each key moment via video broadcasts, which you can watch at:

- https://x.com/AtlanticCouncil?lang=en&utm_campaign=20364194-AC-Intel-Daily-Newsletter&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=403489441

- https://www.facebook.com/AtlanticCouncil/?utm_campaign=20364194-AC-Intel-Daily-Newsletter&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=403489441

- https://www.linkedin.com/company/atlantic-council/?utm_campaign=20364194-AC-Intel-Daily-Newsletter&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=403489441

Selective bibliography

- Munich Security Conference

Munich Security Report 2025: Under Destruction. Munich, 2025. - Munich Security Conference

- Munich Security Report 2025: Under Destruction. Munich, 2025.

- Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2025). NATO, Brussels, 2025.

- Atlantic Council

- NATO Defence Spending Tracker – Transatlantic Security Initiative. Washington D.C., updated 2025.

- The Military Balance 2025. London, IISS/Routledge, 2025.

- Kiel Institute for the World Economy

- Ukraine Support Tracker. Kiel, updated 2025.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- Trends in World Military Expenditure 2024. SIPRI Fact Sheet, 2025.

- Extraordinary European Council Conclusions on Security and Defence. Brussels, 2025.

- EU Strategic Compass for Security and Defence. Brussels, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Defense

- National Defence Strategy of the United States. Washington D.C., 2024.

- House Select Committee on Strategic Competition with the Chinese Communist Party,

- Ten for Taiwan Report. Washington D.C., 2024.

- RAND Corporation

- Deterrence and Defence in the Indo-Pacific. RAND, 2023–2024.

- World Economic Outlook 2025. Washington D.C., 2025.