Artificial Intelligence in Defense: Between Technological Enthusiasm and Operational Reality

ANALYSIS Maritime Security Forum

In a strategic context marked by accelerated technological competition and increasing operational pressures, defense institutions are tempted to view Artificial Intelligence as a quick fix for streamlining processes and supporting decisions. However, the enthusiasm generated by generative models, LLMs, and autonomous agents risks obscuring the essential differences between the fundamental concepts of the AI ecosystem and their actual applicability in the military environment.

To avoid confusion, unrealistic expectations, and misguided investments, a clear understanding of the relationship between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, neural networks, and Deep Learning, as well as the limitations of each component, is necessary. The analysis below provides this structured perspective, highlighting the hierarchy and interdependencies between concepts—an essential step in establishing credible, responsible, and operationally relevant AI capabilities.

Increasingly, governments and defense structures are feeling pressure to adopt Large Multimodal Models (LLMs) and AI agents for decision automation. While such technologies help with documentation, analysis, and reducing administrative tasks, they cannot replace human judgment and do not understand the operational context or moral consequences. The data they process may be incomplete or manipulated, and their excessive involvement in decision-making poses serious risks related to accountability and validation. Perhaps here we can draw a comparison with the use of archaic empirical coefficients in staff calculations or those for the use of certain types of weapons and systems. These coefficients, or even calculation formulas, established empirically (sometimes for a specific purpose), distort reality or direct it towards a certain result.

In defense, truly valuable AI is found in systems such as sensor fusion, pattern recognition, or EW-resistant processing—solutions that require rigorous integration, testing, and governance. Reducing AI to the use of LLM creates false expectations and can lead to misallocation of resources.

Sometimes questions and answers arise such as: “Why doesn’t it work faster?” – “Because this is war.”

We also need to be honest about governance. Who owns it? Who secures it? Who integrates it? Are updates made through audits? Is it tested against adversary manipulation? But without clear answers, the risk increases!

And even if he doesn’t admit it, those of us who are not specialists in the field need literacy.

A real understanding of the AI ecosystem. What different models do, where they are included or not.

Defense AI is not about LLM or agents.

Defense AI is about systems, data, governance, integration, doctrine, leadership.

Innovation, AI tools, autonomy matter, but without foundations, it becomes a burden.

If we want reliable artificial intelligence that is ready to plan a mission, we need to stop chasing buzzwords and start building real capabilities based on operational reality, policy constraints, and long-term accountability.

This is hard work, but it is work that actually protects lives.

However, for a better understanding, it is necessary to analyze the example below as a whole.

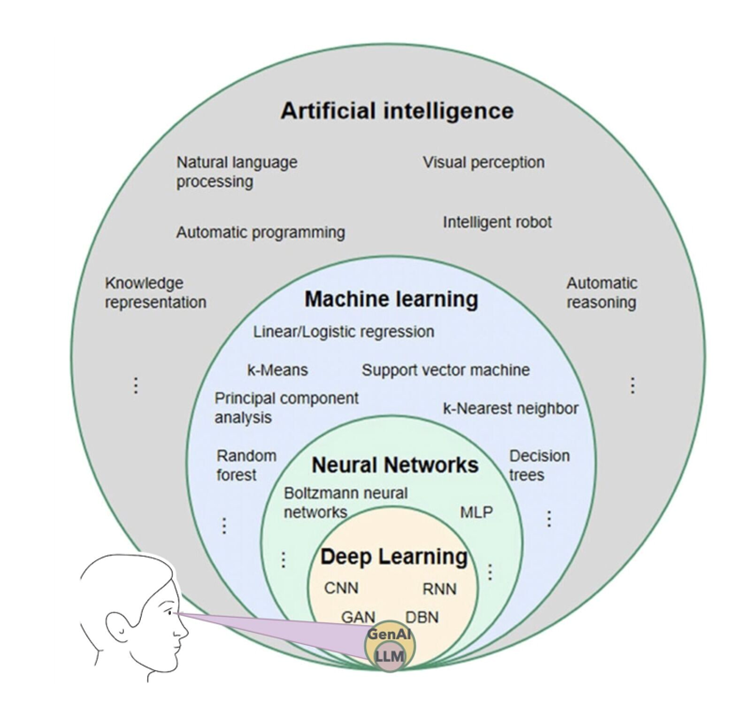

The image above shows the relationship between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, Neural Networks, and Deep Learning in the form of concentric circles, organized from general to specific. On the outside is Artificial Intelligence, the broadest field, which includes all technologies that enable systems to simulate human intelligence. This encompasses areas such as natural language processing, visual perception, intelligent robots, automated reasoning, knowledge representation, and automated programming. Therefore, Artificial Intelligence is the “umbrella” that integrates all these fields.

Inside it is Machine Learning, a subfield of Artificial Intelligence that allows systems to learn from data and improve their performance without being explicitly programmed for each situation. Classic Machine Learning methods include linear and logistic regression, the k-Means algorithm, Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN), decision trees, Random Forest, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Machine Learning is one of the main ways in which systems become “intelligent.”

An important component of machine learning is neural networks, models inspired by the functioning of the human brain. Examples mentioned in the image include MLP (Multi-Layer Perceptron) and Boltzmann neural networks. These are a special type of machine learning algorithms capable of identifying complex patterns in data.

Within neural networks lies Deep Learning, a subcategory characterized by the use of multi-layered networks (hence the term “deep”). Types of Deep Learning models include CNN (Convolutional Neural Networks), RNN (Recurrent Neural Networks), GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks), and DBN (Deep Belief Networks). Deep Learning is used in modern applications such as facial recognition, machine translation, and text generation.

The figure also suggests that GenAI or LLM (language generative models) systems use Deep Learning techniques to interpret and generate information, simulating human perception and understanding.

In conclusion, the relationship between concepts is hierarchical: Artificial Intelligence includes Machine Learning, which includes Neural Networks, and these include Deep Learning. The further we move into the circles, the more specialized and complex the methods become.

We need to study the hierarchy, understand the terms used and their meaning, but above all, the interdependence between them. This is difficult for the uninitiated, but essential for using them correctly.

Artificial Intelligence in maritime defense: between technological promise, operational constraints, and strategic responsibility

The contemporary maritime environment is one of the most complex security spaces of the 21st century. Characterized by geographical vastness, low information density, legal ambiguity, and the simultaneous presence of state and non-state actors, the maritime domain imposes operational requirements that are distinct from those of land or air. In this context, Artificial Intelligence is often presented as the solution capable of fundamentally transforming the way surveillance, early warning, critical infrastructure protection, and naval operations are conducted.

This promise, although partially justified, is often accompanied by technological enthusiasm that risks ignoring the specific realities of the maritime environment. Unlike other operational domains, the maritime environment is dominated by uncertainty, information latency, sensor degradation, and severe logistical constraints. Under these conditions, the implementation of AI cannot be treated as an exercise in accelerated digitization, but rather as a strategic, gradual, and deeply integrated doctrinal process.

Institutional pressure to rapidly adopt AI solutions is increasingly visible in the field of maritime defense. The emergence of generative models, Large Language Models, and autonomous systems has created the perception that naval decision-making can be almost completely automated, accelerated, and optimized. In practice, these technologies are particularly useful for information support activities, textual data analysis, operational document management, or the synthesis of information from multiple sources. They can support the decision-making process, but they cannot replace it.

Generative models do not possess maritime situational awareness, do not understand the legal dynamics of international waters, cannot assess the ambiguity of a naval actor’s intentions, and cannot anticipate the political and strategic consequences of an action at sea. Their operation is based on statistical correlations, not semantic understanding or contextual judgment. In an environment where a wrong decision can quickly escalate a crisis, this limitation becomes critical.

From a historical perspective, the temptation to overestimate decision support tools is familiar to the naval environment. Maritime operations planning has always used models, empirical coefficients, and standardized estimates to manage uncertainty. These tools have been necessary, but never sufficient. Artificial Intelligence does not eliminate this reality, but amplifies it. An insufficiently validated or poorly integrated AI model can produce seemingly coherent but deeply misleading results at a rate that exceeds human capacity for correction.

The real value of Artificial Intelligence in maritime defense manifests itself in less visible but essential areas. Multisensor fusion, correlating data from radar, sonar, AIS, satellite imagery, and ISR sources, allows for the construction of a more coherent common maritime picture. Recognition of navigation patterns, identification of abnormal behavior, and decision support in high-data-volume conditions are areas where AI can bring real operational advantage. Likewise, the ability to operate in conditions of information degradation, electromagnetic interference, or cyber attack is crucial in a contested naval theater.

However, the maritime environment remains dominated by friction and uncertainty. The question frequently asked in operational structures—why a system does not work faster or more accurately—often reflects a misunderstanding of the nature of naval conflict. The sea is not a fully controllable space, and AI cannot eliminate the adversarial, unpredictable, and dynamic nature of maritime operations. Any technology that promises total control over the maritime environment is, by definition, problematic.

In this context, the issue of AI governance becomes central to maritime defense. The implementation of intelligent systems raises fundamental questions related to data ownership, architecture security, integration with existing systems, and responsibility for errors or failures. In the naval environment, where operations are often multinational and conducted in complex legal spaces, the lack of clear governance can create significant strategic vulnerabilities.

Human control remains an indispensable element of AI use in maritime defense. Human-in-the-loop or human-on-the-loop principles are not mere ethical formulas, but operational mechanisms for maintaining responsibility, legitimacy, and compliance with international law. Naval decision-making involves not only tactical efficiency, but also an assessment of proportionality, the risk of escalation, and the impact on the maritime environment and civilian navigation.

Another often overlooked aspect is the AI literacy of personnel involved in maritime defense. Most commanders and decision-makers are not artificial intelligence specialists, nor do they need to be. However, the lack of a functional understanding of how these systems operate creates a dangerous gap between technology providers and operational users. AI literacy means the ability to understand the limitations, ask the right questions, and integrate the technology critically and responsibly.

Clarifying the conceptual hierarchy of Artificial Intelligence is essential in this endeavor. AI is the general framework that includes multiple subdomains, of which Machine Learning is the most relevant for current maritime applications. Neural networks and Deep Learning are used where data complexity requires it, and generative models are only a subcategory, useful mainly for informational and analytical support. Confusing this subcategory with the entire AI ecosystem leads to unrealistic expectations and erroneous strategic decisions.

Ultimately, Artificial Intelligence in maritime defense should not be viewed as a substitute for human competence, naval experience, or strategic leadership. It is a powerful tool, capable of amplifying both performance and errors. Its value depends on how it is integrated into systems, the quality of governance, the existence of human control, and the assumption of long-term responsibility.

Giving up the fascination with quick fixes and investing in real capabilities, tailored to the specificities of the maritime environment, is the only sustainable path to reliable artificial intelligence. It is a slow, difficult, and often invisible process. But it is the process that ultimately contributes to maritime security and the protection of lives at sea.

CONCLUSION

Artificial Intelligence is not a miracle solution, but a powerful tool that amplifies both competence and errors. In defense, its value depends on integration, governance, control, and accountability.

Moving away from buzzwords and investing in real capabilities tailored to operational reality is the only path to trustworthy AI.

This is difficult, slow, and often invisible work. But it is work that ultimately protects lives.

MARITIME SECURITY FORUM