| The Maritime Security Forum is pleased to provide you with a product, in the form of a daily newsletter, through which we present the most relevant events and information on naval issues, especially those related to maritime security and other related areas. It aims to present a clear and concise assessment of the most recent and relevant news in this area, with references to sources of information. We hope that this newsletter will prove to be a useful resource for you, providing a comprehensive insight into the complicated context of the field for both specialists and anyone interested in the dynamics of events in the field of maritime security. |

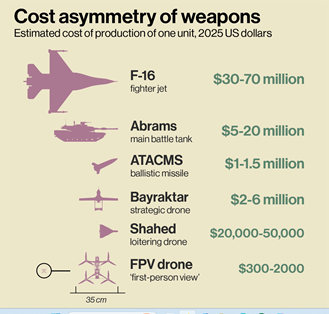

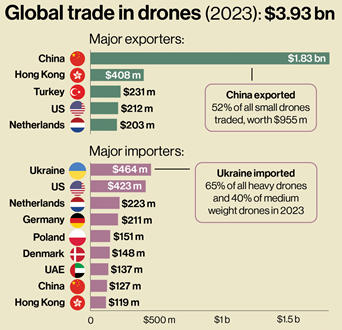

Why US Risk a $100M F-35 on a $70k Iranian Drone?

MS Daily brief-11 February 2026

- MS Daily Brief-en

- The multi-domain deadlock in the context of Romania and the Black Sea

- Integrated military cooperation for the protection of offshore energy platforms in the Black Sea

- NAVY ARSENAL – Explanatory Memorandum

- The Phantom Fleet and maritime security challenges

- China’s military leadership faces a serious problem

- The possibility of Romania initiating a project similar to Nordic-Baltic Eight

Contents

News from Ukraine | Wow! Ukraine has launched a major counterattack! Is this a good idea? 1

Norwegian defence chief says Russia could invade the country to protect its nuclear assets 1

EU moves closer to creating offshore centres for migrants and asylum seekers. 3

“Red alert” for Greece after air force officer accused of spying for China. 6

Iran’s secret fleet of old oil tankers is a ticking time bomb for marine life, experts say. 10

Bulgaria rocked by mysterious deaths of six people in the mountains. 17

The world’s major straits: Strategic maritime chokepoints in global trade. 19

The irregular war of cetaceans in Russia’s North Atlantic. 23

Conventional forces will never embrace irregular warfare. 27

The stop at the Ream naval base reflects the deepening ties between Cambodia and the US 35

Ukrainian Magura V5 marine drones receive a swarm of bait, ready to attack. 36

Ukrainian Magura V5 marine drones receive a swarm of lures, ready to attack. 38

How Artificial Intelligence could reshape four key competitions in the war of the future. 39

Europe’s first private hypersonic rocket reaches Mach 6. 43

Royal Navy showcases AI-accelerated targeting cycle. 44

Lockheed unveils Lamprey submarine drone carrier concept 45

US Navy deploys two nuclear attack submarines near Guam as tensions in the Indo-Pacific rise 46

French Navy launches offshore patrol vessel PH Trolley de Prévaux to secure Atlantic approaches 47

US Air Force deploys A-10C Warthogs to protect Navy mine warfare operations in the Arabian Gulf 50

Taiwan to build 10 new light frigates for air defence and anti-submarine warfare. 52

Frankenburg to test anti-drone missile in Ukraine in 2026. 55

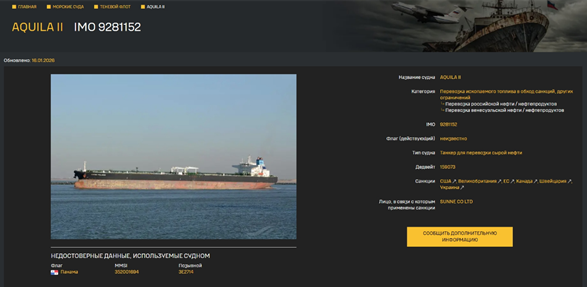

US intercepts Russian Shadow Fleet tanker Aquila II. 56

BREAKING NEWS: Iran FORTIFIES nuclear facility as US considers attack; IDF ELIMINATES terrorist leader | TBN Israel

News from Ukraine | Wow! Ukraine has launched a major counterattack! Is this a good idea?

Norwegian defence chief says Russia could invade the country to protect its nuclear assets

Exclusive: Eirik Kristoffersen, who served in Afghanistan, rejects Trump’s claim that NATO troops stayed out of the front line

Shaun Walker in Bergen

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 20:07 CET

The Norwegian army chief has said Oslo cannot rule out the possibility of a future Russian invasion of the country, suggesting Moscow could act on Norway to protect its nuclear assets stationed in the far north.

“We do not rule out a land grab by Russia as part of its plan to protect its own nuclear capabilities, which are the only thing they have left and which effectively threaten the United States,” said General Eirik Kristoffersen, the Norwegian defence chief.

He acknowledged that Russia has no ambitions to conquer Norway, as it did in Ukraine or other territories of the former Soviet Union, but said that much of Russia’s nuclear arsenal is located on the Kola Peninsula, a short distance from the Norwegian border, including nuclear submarines, land-based missiles and nuclear-capable aircraft. These would be crucial if Russia were to enter into conflict with NATO elsewhere.

“We do not rule out this possibility, because Russia still has the option to do so to ensure that its nuclear capabilities, its retaliatory capabilities, are protected. This is the scenario we are considering in the far north,” he said.

In a wide-ranging interview with the Guardian newspaper, Kristoffersen harshly criticised Donald Trump’s recent comments about Greenland, as well as the US president’s “unacceptable” claims that allied countries did not serve on the front lines in Afghanistan while American troops bore the brunt of the fighting.

“What he said made no sense, and I know that all my American friends in Afghanistan know that,” said Kristoffersen, 56, a career officer who has participated in several missions in Afghanistan.

“We were definitely on the front lines. We did all the missions, from arresting Taliban leaders to training Afghans and doing surveillance. We lost 10 Norwegians. We lost friends there. So we all felt it didn’t make sense,” he said.

“At the same time, I felt that this is President Trump. I’ve never seen him in Afghanistan. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about when he says these things. A president shouldn’t say such things, but that didn’t really affect me. But my concern was for the Norwegian veterans, for the relatives of those we lost, for the soldiers we lost.”

Kristoffersen has been Norway’s chief of defence since 2020, responsible for the country’s armed forces as well as its intelligence service. It has been a period of intense change, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced a rethink of European security, with neighbouring Sweden and Finland joining Norway in the NATO alliance and the country strengthening its border areas with Russia in the far north.

Kristoffersen said that although Norway is mindful of the threat of a traditional Russian invasion, Russia’s current tactics are more diffuse. “If you prepare for the worst, nothing prevents you from being able to counter sabotage and more hybrid threats,” he said.

He added, however, that Norway and Russia still maintain some direct contact regarding search and rescue missions in the Barents Sea and that regular meetings take place at the border between representatives of the two armies.

He recommended setting up a direct military telephone line between the two capitals to provide a channel of communication that would prevent conflicts from escalating due to misunderstandings. He said that Russia’s actions in the far north have generally been less aggressive than those in the Baltic Sea.

“So far, what we have seen in terms of airspace violations in our area have been misunderstandings. Russia conducts a lot of [GPS] jamming operations, and we believe that the jamming also affects their aircraft,” he said.

“They haven’t said that, but we observe that when something like an airspace violation happens, it’s usually due to the pilots’ lack of experience. When we talk to the Russians, they respond in a very professional and predictable manner.”

Regarding Norway’s northern territory of Svalbard, which includes a Russian settlement and cannot be militarised under the terms of a 1920 treaty, Kristoffersen said that Russia “respects the treaty” and that Norway has no intention of militarising the area.

Moscow has accused Oslo of secretly militarising Svalbard, but Kristoffersen said this is just propaganda that Moscow does not really believe.

The northern Norwegian territory of Svalbard contains a Russian settlement. Photo: Anadolu/Getty Images

Regarding Trump’s claim that China and Russia have military plans in Greenland, Krisoffersen said it was “very strange” to hear such claims.

“We have a very good picture of what is happening in the Arctic from our intelligence service, and we don’t see anything like that in Greenland… we see Russia’s activity with its submarines and also its underwater programme in the traditional part of the Arctic… but it’s not about Greenland, it’s about reaching the Atlantic,” he said.

His comments came as French President Emmanuel Macron told a group of European newspapers that Europe was at a “Greenland moment” and urged countries to stand up to Trump.

Macron said that when there is “blatant aggression… we must not bow our heads or try to reach an agreement. We have tried this strategy for months and it does not work. But above all, it leads Europe, strategically, to an increase in its dependence.”

He said fears over Greenland were far from over. “There are threats and intimidation, and then suddenly Washington backs down. And we think it’s over. But don’t believe that for a second,” he said.

Asked whether Denmark and its allies would have any chance of repelling a US military takeover of Greenland if Trump went ahead with the plan, Kristoffersen replied: “They won’t, so it’s a hypothetical question.”

But he added a warning for Trump and the US military. “If Russia has learned anything from the war in Ukraine, I think it’s that it’s never a good idea to occupy a country. If the people don’t want it, it will cost you a lot of money and effort, and in the end, you will lose.

“The initial occupation is often very easy, but maintaining the occupation is very, very difficult. And I think all expansionist powers have experienced this.”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/feb/10/norway-defence-chief-russia-nuclear-assets

EU moves closer to creating offshore centres for migrants and asylum seekers

MEPs vote to allow people to be deported to places they have never been, while NGOs express fears over new list of “safe third countries”

Jennifer Rankin in Brussels

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 17:38 CET

The EU has moved closer to creating offshore centres for migrants and asylum seekers after centre-right and far-right MEPs joined forces to push for tougher migration policies.

MEPs have voted for legislative changes that will give authorities more options for deporting asylum seekers, including sending people to countries they have never been to.

Under the new rules, which are expected to come into force in June, an asylum seeker can be deported to a country outside the EU, even if they have only passed through it, or to a place with which they have no connection, as long as a European government has signed an agreement with the host country.

The vote effectively supports Italy’s agreement with Albania and the Dutch government’s agreement with Uganda on the deportation of people whose asylum applications in the Netherlands have been rejected.

In a separate vote, MEPs also voted to create an EU list of ‘safe third countries’, meaning that people from these countries will be subject to accelerated procedures and find it more difficult to claim asylum.

The list includes all countries that are candidates for EU membership, including Georgia and Turkey, where the EU has expressed concern about the government’s crackdown on the opposition in 2025. The list of safe countries also includes Bangladesh, Colombia, Egypt, India, Kosovo, Morocco and Tunisia.

Human rights groups have raised concerns about the inclusion of Tunisia, where President Kaïs Saïed has taken repressive measures against civil society and opposition figures have been sentenced to up to 66 years in prison by politically controlled courts. Tunisian forces have also forced migrants to return to remote desert regions, where some have died of thirst.

A coalition of 39 NGOs said in a statement ahead of Tuesday’s vote that designating Tunisia as a safe country of origin deprived “Tunisian citizens of their right to an individual, fair and effective assessment of their asylum claims, while giving the Tunisian authorities a new blank cheque to continue systematic violations against migrants, civil society and civic space in general.”

Alessandro Ciriani, an Italian MEP who led the European Parliament’s work on the list of safe countries of origin, welcomed the result: “This is the beginning of a new phase: migration is no longer endured, but governed.”

He said: “For too long, political decisions on migration policy have been systematically called into question by divergent judicial interpretations, paralysing state action and fuelling administrative chaos.”

Ciriani is a member of Giorgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party, which has clashed with Italian and European judges who ruled against the government’s agreements with Albania.

In 2024, an Italian court ruled that seven men from the Albanian centre would be transferred to Italy, disagreeing with Italy’s argument that it was a safe country of origin.

Italy argued that the men could be transferred to their “safe” countries of origin, Bangladesh and Egypt, but the judges said there was a lack of transparency in how safety had been assessed.

The EU has tightened its rules on refugees since more than 1.3 million people sought asylum during the 2015 migration crisis, but the trend has accelerated with the electoral gains of nationalist and far-right parties.

In search of “innovative solutions,” EU leaders approved the concept of offshore return centres in 2024 — processing centres for people who have been denied asylum in the EU.

The right-wing Dutch government announced last September that it had reached an agreement with Uganda to allow the deportation of Africans who had been denied asylum in the Netherlands. The social-democratic government in Denmark had previously explored the possibility of processing asylum seekers in Rwanda, but never followed through with the project.

Last year, 155,100 people risked their lives travelling in unseaworthy boats across the Mediterranean Sea, and 1,953 died or disappeared, according to the UN refugee agency.

The death toll continued in the first weeks of 2026. It is feared that up to 380 people drowned after a boat from Tunisia was caught in a cyclone last month.

Supporters of the new measures argue that they undermine the business model of human traffickers.

“People who really need protection must receive it, but not necessarily in the European Union. Effective protection can also be provided in a safe third country, while individual assessment remains fully guaranteed,” said Assita Kanko, a Flemish nationalist politician.

The International Rescue Committee described the votes as deeply disappointing.

“The new ‘safe third country’ rules will likely force people to go to countries they have never set foot in – places where they have no community, do not speak the language and face a very real risk of abuse and exploitation,” said Meron Ameha Knikman, senior advocacy adviser at the IRC.

The two laws were passed with strong support from the centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and three nationalist and far-right groups.

The votes were the latest sign of a new dynamic in the European Parliament after a record number of nationalist and far-right MEPs were elected to the traditional Christian Democrats in 2024.

While critics accused the EPP of breaking the cordon sanitaire, the voting lists revealed a more complex picture. The centre-left was deeply divided, with significant minorities of socialist and centrist MEPs voting in favour of the new laws, while many centrists abstained.

“Warning sign” for Greece after air force officer accused of spying for China

Christos Flessas was detained in a case considered to be an exposure of Beijing’s strategy to infiltrate Western military and security services

Helena Smith in Athens

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 20:04 CET

A Greek air force officer arrested on suspicion of spying for China has been remanded in custody pending trial after appearing before a military judge in a case seen as exposing Beijing’s determination to infiltrate Europe’s security and intelligence services.

Surrounded by armed escorts, a squadron commander identified as Colonel Christos Flessas left the court on Tuesday evening after testifying for more than eight hours.

The 54-year-old could face life imprisonment if found guilty of charges that include “passing strictly confidential military information” to China. He is said to have had access to sensitive military information, including developing armed forces technologies, and is believed to have been recruited by Beijing last year.

Greek media reported that he admitted to photographing and transmitting classified NATO documents using specialised encryption software provided by the Chinese secret services . He is alleged to have undergone training in China during an undeclared trip to that country, which, according to military sources, ultimately exposed him.

In a statement made by his lawyer after appearing in court, Flessas said: “Without my knowledge and without intention, I was involved in something that turned into a nightmare, dangerous and illegal. In my testimony, I did not try to justify myself or even defend myself… I ask to be punished with a fair sentence.”

The Greek authorities were reportedly informed by the CIA about the extent of the information leak, and in an extremely unusual statement after Flessas’ arrest on 5 February, the Greek general staff said there was “clear evidence of criminal offences under the military criminal code”.

Chinese agents are believed to have initially approached their target online before recruiting him at a NATO conference in an unidentified European country. Flessas reportedly said he was lured with promises of financial rewards in foreign currency and digital payments of between €5,000 and €15,000 for each transmission made. He told the military magistrate on Tuesday that the first contact with the agents who led him to his superior was established through LinkedIn.

Nicholas Eftimiades, a retired senior American intelligence officer with considerable experience in Chinese espionage operations, told the Guardian that the case was a wake-up call for the Greek government and military.

“[It is] significant because it shows China’s willingness and ability to penetrate the military communications infrastructure of Greece and other NATO members,” he said. “Nations spy on other armies to gain an advantage in war. Despite all the declarations of friendship and economic engagement, China continues to evolve as a threat to democracies around the world.”

Flessas was previously a NATO assessor in information systems and, at the time of his arrest, commanded a battalion in the Athenian suburb of Kavouri, specialising in telecommunications.

Eftimiades, whose book Chinese Espionage Operations and Tactics was released last year, said that because Chinese citizens are required by law to support their country’s espionage efforts, the West is increasingly vulnerable to spies from Beijing.

Last week, four people, including two Chinese nationals, were arrested in France on suspicion of intercepting and collecting military information. In Germany last September, a former assistant to a member of parliament from the far-right Alternative für Deutschland party was sentenced to nearly five years in prison for spying for China.

“China uses a ‘whole-of-society’ approach to conduct espionage worldwide,” said Eftimiades, who currently teaches national security at Penn State University. “[This] is different from the efforts of any Western government. The sheer volume of activity makes it impossible to counter… Western societies are open democracies. This makes them extremely vulnerable to China’s covert influence efforts.”

Media reports on Tuesday suggested that the Greek air force officer is cooperating fully with authorities. Well-informed sources said there are fears that other military officials may also be involved. One of them said the armed forces had made the case public as a warning.

“What we are seeing is unprecedented,” said Plamen Tonchev, an expert on Sino-Greek relations. “Greece is considered a relatively friendly country to China. This is the first time China has been so openly involved in an espionage case of this kind.”

Tonchev said the episode would “tarnish the image” of Beijing in a country where it gained control of a large part of the port of Piraeus a decade ago.

An estimated 24% of China’s imports to Europe are transported through container terminals in Piraeus, and Tonchev said this is a source of “great pride” for Beijing.

Iran asks the US not to allow Netanyahu to thwart nuclear negotiations before meeting with Trump

Tehran’s intervention comes as the Israeli prime minister heads to a hastily arranged meeting at the White House

Patrick Wintour Diplomatic Editor

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 20:34 CET

Tehran has called on the US not to allow Israel to destroy the chance of reaching an agreement on Iran’s nuclear programme, amid speculation that Benjamin Netanyahu intends to use Wednesday’s hastily arranged meeting with Donald Trump at the White House to derail the negotiations.

Iran’s intervention came as the Israeli prime minister travelled to Washington to convince Trump not to negotiate an agreement with Tehran if it excludes limiting the country’s ballistic missile programme, renouncing support for proxy forces in the region and reducing human rights abuses in the country.

Netanyahu is deeply concerned that Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and his special envoy, Steve Witkoff, are prepared to conclude an agreement limited to restricting Iran’s nuclear programme, which, in Israel’s view, would do nothing to reduce the long-term threat that Tehran poses to the region.

Before leaving for Washington, Netanyahu said he would “present to the president our approach to our principles in the negotiations.” He is expected to provide Trump with new information about Iran’s military capabilities, including new long-range ballistic missiles.

Netanyahu faces a delicate task in establishing his position, as he risks being perceived as provoking two of Trump’s most respected advisers by drawing up a series of demands that could force the US into a prolonged conflict with Iran.

He also risks upsetting Trump by creating divisions within the Republican Party, especially if he reminds the US president of his repeated and unfulfilled promises to come to the aid of Iranian protesters.

Netanyahu’s turbulent relationship with Trump is already entering another difficult period, as he continues to block his peace plan for Gaza, banning a Palestinian technocratic body from entering the Gaza Strip and effectively attempting to annex the West Bank.

Signalling that he knows he is on shaky ground, Netanyahu agreed to take US Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee with him. Before leaving for Washington, Huckabee said there was “extraordinary alignment between the US and Israel on Iran” and that, as far as he knew, the two sides shared the same red lines.

Iran expressed its anger at Israel’s intervention. Ali Larijani, head of the Supreme National Security Council, the body that oversees Tehran’s negotiating strategy, said: “The Americans should think wisely and not allow him, through his attitude, to create the impression before his flight that he is going to the United States to set the framework for nuclear negotiations. They must remain vigilant about Israel’s destructive role.”

Larijani met with mediators between Washington and Tehran in Muscat to discuss the agenda for the upcoming negotiations.

Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman Esmail Baghaei said at the weekly press conference: “Our side in the negotiations is America. America must decide to act independently of the destructive pressures and influences that are harmful to the region.”

Israel’s alarm over a potential deal that undermines its ambitions for regime change in Tehran has grown since the US agreed to reopen indirect negotiations with Iran, which began on Friday in Oman.

The Iranian government also faces internal political challenges, with several reformist groups and academics issuing statements protesting against the suppression of dissent and, in particular, the arrest of Reformist Front leaders.

The Front issued a new statement expressing its shock and warning that the regime’s exclusionary approach and baseless accusations will exacerbate the political impasse and “strengthen the violent and belligerent factions that support Israel.” The Front called on Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian to intervene urgently to secure the release of its leaders.

Even if the planned second round of negotiations is limited to Iran’s nuclear programme, as Tehran wishes, there is no guarantee of success, as Iran insists on retaining its right to enrich uranium as fuel for nuclear power plants, which the US allowed under the 2015 agreement, but which Trump seems to be ruling out.

Trump sent the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln and three accompanying warships to the region, which are capable of striking a wide range of Iranian military and economic targets. The US has also strengthened the air defences of American bases in the region.

The head of Iran’s atomic energy authority said Tehran may be prepared to dilute its stockpile of highly enriched uranium to a purity of 60%, a limited concession given that the 2015 agreement limited enrichment to a purity of 3.75%.

Iran’s secret fleet of old oil tankers is a ticking time bomb for marine life, experts say

Exclusive: Analysts say an oil spill catastrophe is coming that could be far worse than the Exxon Valdez disaster

Damian Carrington Environment Editor

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 12:50 CET

Decrepit oil tankers in Iran’s secret fleet, which violate sanctions, are a “time bomb,” and it is only a matter of time before a catastrophic environmental disaster occurs, maritime intelligence analysts have warned.

Such an oil spill could be far worse than the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, which released 37,000 tonnes of crude oil into the sea, they said.

Pole Star Global assessed 29 Iranian ships that disappeared from radar after turning off their satellite identification systems following the US seizure of a Venezuelan tanker in December. Half of them were older than the recommended 20-year lifespan, analysts said, and because they operate in the shadows, they are believed to be poorly maintained and may not comply with international safety standards.

In recent years, more than 50 incidents involving tankers around the world have been reported, ranging from collisions to oil spills. Nine oil spills, from Thailand to Italy and Mexico, were attributed to ships in the Russian fleet between 2021 and 2024. However, the Iranian fleet has been little analysed.

The new analysis placed seven of the 29 ships in the “extreme risk” category, being over 25 years old, while three were over 30 years old. Five ships were both old and in the “very large crude carrier” class, capable of carrying around 300,000 tonnes of oil.

The hidden fleet’s tankers were typically uninsured, analysts said, meaning that the cost of cleaning up a spill would fall to the country where the disaster occurred. That cost could be between $860 million and $1.6 billion, according to a recent estimate.

The total fleet of tankers in the hidden fleet is estimated at several hundred ships, with some estimates suggesting that they account for 17% of the global tanker fleet. Russia has the largest hidden fleet, and two old Russian tankers caused a major spill in the Black Sea in December 2024 after one sank and the other ran aground.

Two Russian tankers sink in the Black Sea, causing a spill of 4,300 tonnes of oil – video

Saleem Khan, head of data and analytics at Pole Star Global, said Iran’s unauthorised fleet has some of the oldest tankers in any fleet, with some far exceeding the safe lifespan for such vessels.

“It’s like a ticking time bomb,” he said, adding that it was “only a matter of time” before one of them sank and broke apart, or an explosion led to a major oil spill. “They carry oil, often under pressure, and there are a lot of machines on board that have to work perfectly so that problems such as fire or explosion don’t occur,” Khan said.

“The important thing is just the scale of the disaster it could cause – it could be many times greater than that caused by the Exxon Valdez. But it’s a very, very profitable business for all involved. So they have a vested interest in keeping it going.”

Mark Spalding, president of the Ocean Foundation, said: “Iran’s ghost fleet poses a significant and growing threat to the environment. The question is not whether a major incident will occur, but when and which coastal communities and marine ecosystems will pay the price for a shipping system designed to avoid responsibility.

“We are deeply concerned that the environmental dimension of the ghost fleet’s operations has not received sufficient attention.”

The Iranian government did not respond to a request for comment.

Ghost fleet vessels use deceptive practices such as false flags, fake owners and blocked or falsified AIS satellite tracking to transport sanctioned goods. The trade in sanctioned oil is estimated to be worth many billions of dollars a year. French President Emmanuel Macron said in October that Russia’s ghost fleet trade was worth €30 billion a year and was financing 30-40% of the war in Ukraine.

The United States has been most active against the ghost fleet tankers, seizing ships linked to Russia and Venezuela in recent months. France, Germany, Estonia and other countries have physically intercepted ghost fleet ships. The UK has not done so, despite the fact that the English Channel is a bottleneck for maritime transport, which is obliged to pass through national territorial waters.

However, the UK threatened to seize a tanker from the hidden fleet linked to Russia last week. In January, the US tracked the Russian-linked tanker Marinera from the Caribbean to the North Atlantic, seizing it between Scotland and Iceland with British assistance.

Pole Star Global’s analysis of Iran’s hidden fleet of tankers concluded: “The combination of the advanced age of the vessels, the lack of Western insurance and reduced maintenance standards under sanctions creates a high risk of catastrophic environmental damage.”

A single incident involving one of the larger tankers would, according to the report, result in toxic oil spills covering thousands of square kilometres, mass mortality of marine life, contamination of 500-1,000 miles or more of coastline, and a severe impact on human health and livelihoods.

The report recommends improving satellite monitoring systems for tracking ships and stricter port inspections, including refusing entry to ships that cannot demonstrate their safety. It also advocates sanctions against beneficial owners of high-risk ships. But Khan said: “There is certainly no coordinated international effort.”

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) is responsible for setting the regulatory framework applied by member states. A spokesperson said: “Ships that do not comply with IMO safety and environmental regulations or operate without transparency endanger seafarers, the marine environment and global trade.”

The IMO’s Legal Committee is reviewing existing international maritime rules and agreements to see how they can be used more effectively to stop illegal activities and is developing clear guidance on how ships should be registered, focusing on better background checks, greater transparency and closer cooperation between countries to prevent false registrations and false flags.

A spokesperson for the British government said: “The United Kingdom is committed to disrupting and deterring vessels in the ghost fleet. We continue to take robust action, including requesting proof of insurance and penalising vessels suspected of being part of the ghost fleet transiting the English Channel. Since October 2024, the UK has challenged approximately 600 vessels suspected of being part of the ghost fleet using this system.”

“A step in the wrong direction”: Israel’s plans for the West Bank provoke negative reactions worldwide

The US, UK, EU and Arab countries condemn plans that, according to Israeli ministers, “will destroy the idea of a Palestinian state”

Julian Borger in Jerusalem

Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 02:59 CET

Israeli measures to tighten control over the West Bank have sparked global backlash, including a signal from Washington reaffirming the Trump administration’s opposition to the annexation of occupied territory.

Announcing the measures, which involve extending Israeli control to areas currently under Palestinian administration, Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz said they were aimed at strengthening Israeli settlements in the West Bank and preventing the emergence of an independent sovereign Palestine.

The measures, adopted by the Israeli security cabinet, also facilitate the identification of landowners in the West Bank and the purchase of property in the territory by non-Arabs. It was initially unclear when the new rules would come into force, but they do not require additional approvals.

“We will continue to reject the idea of a Palestinian state,” Katz said in a joint statement with Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich.

The EU called the measures “another step in the wrong direction” and said sanctions were “still on the table,” including the possible suspension of parts of the EU-Israel trade agreement.

A joint statement by a group of Arab and Islamic states, which will be key to Donald Trump’s hopes of implementing a peace plan in Gaza, said they “condemn in the strongest terms Israel’s illegal decisions and measures aimed at imposing illegal Israeli sovereignty.”

The signatories — including Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, Indonesia and Turkey — said the new measures “will fuel violence, deepen the conflict and jeopardise regional stability and security.”

The United Kingdom said it “strongly condemns” the Israeli measures. “Any unilateral attempt to alter the geographical or demographic structure of Palestine is wholly unacceptable and would be incompatible with international law,” the UK said in a statement. “We call on Israel to immediately revoke these decisions.”

The Australian government, which is hosting a visit by Israeli President Isaac Herzog, also joined in the global condemnation. “Australia opposes the decision by Israel’s security cabinet to extend Israeli control over the West Bank. This decision will undermine stability and security,” the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said in a statement. “The Australian government has made clear that settlements are illegal under international law and represent a significant obstacle to peace. Changing the demographic composition of Palestine is unacceptable.

“The two-state solution remains the only viable path to long-term peace and security for both Israelis and Palestinians.”

The outrage over Israel’s actions came on the eve of a planned meeting at the White House between Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump on Wednesday. The administration made no official comment, but a White House official issued a statement to reporters expressing opposition.

“President Trump has made clear that he does not support Israel’s annexation of the West Bank,” the statement said. “A stable West Bank ensures Israel’s security and is consistent with this administration’s goal of achieving peace in the region.”

The new measures are sweeping and directly target authority and control over West Bank territory. They repeal a law dating back to Jordanian rule before 1967 that prohibited the sale of land to non-Arabs.

They also transfer authority over building permits in Hebron from the Palestinian-run municipality to the Israeli Civil Administration, the army’s occupation authority in the territory. The transfer could violate the 1997 Hebron Protocol, which divided the city into two sectors.

The Jewish settlement around Rachel’s Tomb in Bethlehem is also being transferred from Palestinian rule to direct Israeli control.

The Palestinian Authority’s control over designated parts of the West Bank has been severely weakened in recent decades due to lack of money, aggressive obstruction and Israeli settlement construction, as well as its own corruption. It issued a statement in its capital, Ramallah, warning that the new Israeli measures were aimed at “intensifying attempts to annex the occupied West Bank.”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/feb/10/israel-west-bank-plans-global-backlash

Trump news in brief: Why did the FBI raid the Georgia election office? Trump supporters who deny the election results asked them to do so

The unprecedented raid heightens concerns that the president will attempt to interfere in this year’s midterm elections – important US political news from 10 February 2026 in brief

The Guardian team

Wednesday, 11 February 2026, 03:00 CET

When the Federal Bureau of Investigation raided the election office in Fulton County, Georgia, last month, the decision was based on debunked claims by election deniers and came after a complaint from a White House lawyer who tried to overturn the 2020 election, a sworn statement of the search warrant revealed on Tuesday shows.

The FBI investigation “stemmed” from a complaint filed by Kurt Olsen, a lawyer who sought to overturn the 2020 election and contacted Justice Department officials to urge them to file a motion with the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the election. Olsen began working at the White House last year to investigate alleged election fraud.

FBI witnesses in the investigation include a group of conservative activists who have been harassing state officials for years with allegations of wrongdoing in Fulton County. Many of their allegations have been investigated by state officials and debunked.

Other witnesses include two members of the Georgia state election commission, aligned with Trump, whom he publicly praised as “pitbulls” at a 2024 rally. The two members are Janice Johnston and Janelle King, who is married to Kelvin King, the current candidate for Georgia secretary of state.

The unprecedented raid raised concerns that Donald Trump would attempt to interfere in this year’s midterm elections. This concern intensified further when it was revealed that Tulsi Gabbard, the director of national intelligence, was present at the raid in Fulton County. Gabbard is said to be conducting her own investigation, separate from that led by the Department of Justice.

Affidavit reveals that debunked claims by election deniers influenced FBI raid in Georgia

Trump lost Georgia in 2020 by nearly 12,000 votes, a result that has been confirmed twice. However, claims of wrongdoing were central to his efforts to keep alive the myth that the 2020 election was rigged.

Congressmen name six wealthy men ‘likely incriminated’ in Epstein files

Democratic Congressman Ro Khanna said on Tuesday that he and his Republican colleague Thomas Massie had forced the Justice Department to reveal the “hidden” names of six wealthy men they say are “likely incriminated” by their inclusion in the so-called Jeffrey Epstein files.

In a post on X, Khanna, from California, named the six as Salvatore Nuara, Zurab Mikeladze, Leonic Leonov, Nicola Caputo, Sultan Ahmed Bin Sulayem and Leslie Wexner.

“They always gave us the hardest jobs”: how Maga billionaires relied on Mexican labour

When JD Vance gave a speech on the US economy late last year at a Uline factory in Allentown, Pennsylvania, he talked about the Trump administration’s key goals: removing “illegal aliens” from the country, rewarding companies that keep jobs in the US, and paying Americans good wages.

“We’re going to reward companies that build here in America and pay good wages to do so,” Vance said.

The location was not chosen at random. Uline, a privately held, billion-dollar office supply company, is owned by Liz and Richard Uihlein, two of the biggest donors to the Maga Republicans in the 2024 election.

But when it comes to immigration, Uline’s hiring practices in recent years offer an alternative view of how the US economy works in the real world.

Epstein arranged an intimate relationship for Tesla’s Kimbal Musk, emails show

Jeffrey Epstein arranged an intimate relationship between a woman in his network and Kimbal Musk, Elon Musk’s brother and a member of Tesla’s board of directors, according to emails in documents recently released by the Justice Department. The younger Musk and the woman had a relationship for about six months between 2012 and 2013, with Kimbal Musk describing it as “a romantic relationship.”

Local police are assisting ICE by using school surveillance cameras in the context of Trump’s restrictive immigration measures

US police departments are secretly using school surveillance cameras to support Donald Trump’s campaign against mass immigration, according to an investigation by 74.

Hundreds of thousands of audit logs over a one-month period show that police are searching the national database of automatic number plate readers, including from surveillance cameras in schools, for immigration-related investigations.

Mark Carney reminds Trump that Canada paid for the key border bridge that the US president says he will not open

The Canadian prime minister said he had a “positive” conversation with Donald Trump after the US leader threatened to block a key new bridge between the two countries, reminding the president that Canada paid for the construction and that the US owns part of the property.

Former Florida police chief claims Trump told him “everyone” knew what Epstein was doing in 2006

Donald Trump criticised Jeffrey Epstein about two decades ago, claiming that “everyone knew what he was doing,” a former Palm Beach police chief said.

Michael Reiter’s account of a conversation with Trump, contained in the 3 million pages of documents about Epstein released by the Justice Department, contrasts dramatically with the US president’s public statements. After Epstein’s arrest in July 2019, Trump said “I had no idea” when asked if he knew about his former friend’s abuse of teenage girls.

Trump administration removes LGBTQ+ Pride flag from Stonewall National Monument

The New York monument commemorates the June 1969 riots that followed a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay bar in Greenwich Village, Manhattan. The six days of protests against the police action were a key moment in the start of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement, and the site has since become a national symbol of LGBTQ+ pride. It is the latest move by the federal government to end diversity initiatives and sanitise the history shared in national parks.

What else happened today:

The acting director of ICE told a congressional committee on Tuesday that his agency is “an essential part of the overall security apparatus for the World Cup” and refused to commit to suspending operations near matches in this summer’s tournament.

Israel’s moves to tighten its grip on the West Bank have drawn global backlash, including a signal from Washington reaffirming the Trump administration’s opposition to annexing occupied territory.

In a surprise victory that could have implications for Democrats nationally, progressive activist Analilia Mejia was poised Tuesday to win a special primary election for a seat in the New Jersey House of Representatives after her main opponent conceded defeat.

Susan Collins, the Republican senator from Maine, who is one of the Democrats’ main targets in this year’s midterm elections, launched her campaign for a sixth term on Tuesday.

A new Republican bill proposes sweeping changes to U.S. toxic chemical laws that would eliminate protections for consumers, workers and the environment, warn public health advocates mobilising against the legislation.

US Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick had lunch with Jeffrey Epstein on the disgraced financier’s private island, he said on Tuesday, as he faces mounting calls for his resignation from lawmakers on both sides of the political spectrum.

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2026/feb/10/trump-administration-news-updates-today

Bulgaria rocked by mysterious deaths of six people in the mountains

The case is shrouded in feverish speculation, with prosecutors saying autopsies show two of the victims were “probably” murdered

Eden Maclachlan in Sofia

Tuesday, 10 February 2026, 18:13 CET

It has been dubbed Bulgaria’s “Twin Peaks”: a sinister saga involving the mysterious deaths of six people in the middle of the mountains that has gripped the Eastern European country.

Zahari Vaskov, director of the General Directorate of the National Police, said at a press conference on Monday that these deaths are “an unprecedented case in our country.”

Perhaps fitting for an investigation shrouded in sensational conspiracies, conflicting accounts and feverish speculation, Borislav Sarafov, the chief prosecutor, gave his own verdict. “Life has given us more shocking details here than in the TV series Twin Peaks,” he told local media, alluding to the 1990s American television series.

The case began in early February when three men aged 45, 49 and 51 were found dead in the burnt remains of a cabin near the Petrohan Pass, a mountain pass linking the province of Sofia to the northwestern province of Montana.

All three had gunshot wounds to the head, which forensic experts said were apparently self-inflicted, either from a short or close range. DNA traces detected on the firearms belonged only to the deceased men, they said.

Then, on Sunday, police discovered the bodies of three more people, two men aged 51 and 22 and a 15-year-old boy, in a caravan near the Okolchitsa peak, about 100 km north of the capital Sofia. The three had been sought by law enforcement because investigators suspected they were connected to the deaths in the Petrohan Pass.

Agence France-Presse reported that the prosecutor’s office said on Tuesday: “Based on the autopsy data for the three bodies [found later], it appears that there were probably two murders committed in succession and a suicide.”

According to the police, five of the deceased were members of the National Agency for the Control of Protected Areas, a non-governmental organisation dedicated to nature conservation, which used the hut in the Petrohan Pass as its headquarters and also hosted rural holiday camps for young people.

Some reports described its members as “forest rangers” who had been patrolling the area near the Serbian border for years and assisting the border police. Meanwhile, law enforcement officials said the men were involved in Tibetan Buddhism and quoted a relative of one of the members’ , who spoke of “exceptional psychological instability” within the group.

People close to the deceased said they must have been killed because they witnessed criminal activity in the Bulgarian-Serbian border area, where human trafficking and illegal logging are not uncommon.

Ralitsa Asenova, the mother of one of the victims found in the caravan, dismissed reports of tensions within the group. “It is obvious that they witnessed something. For me, this is a crime committed for professional reasons,” she said in an interview with Bulgarian television station Nova.

With details still scarce, the lack of official information has led to the spread of often unfounded speculation online and further undermined Bulgarians’ already low trust in their institutions and authorities. The country has no government and is heading for its eighth parliamentary election in five years.

Former President Rumen Radev described the case as “a political shock and a sign of the state of the country,” according to his press office. Radev, who resigned as head of state last month after nine years in office, offered his condolences to the families of the deceased and urged the authorities to resolve the case.

“I will not comment on this tragedy, which must be investigated by the competent authorities. The causes of these crimes must be clarified as soon as possible, because the public is waiting for answers,” he said.

In 2024, a survey showed that 70% of Bulgarians believed in conspiracy theories, while 37% were victims of disinformation – to such an extent that the authors of the study, conducted by the Centre for the Study of Democracy (CSD) and the Bulgarian-Romanian Digital Media Observatory, claimed that Bulgaria was in a “post-truth” situation.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/feb/10/bulgaria-mysterious-deaths-mountains-petrohan-pass

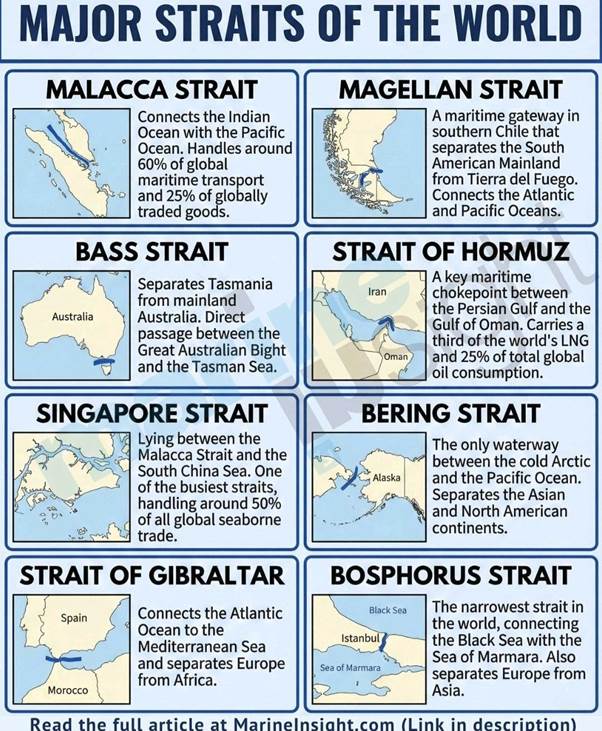

The world’s major straits: Strategic maritime chokepoints in global trade

Sea straits function as critical nodes in the global transport network, facilitating international trade, energy flows and geopolitical connectivity.

The Strait of Malacca

Connecting the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, the Strait of Malacca is one of the world’s most critical maritime routes. It handles nearly 60% of global maritime traffic and approximately 25% of globally traded goods. Due to its narrow width and shallow depth, it is extremely vulnerable to congestion, piracy and navigation risks, making it a strategic concern for global supply chains.

The Straits of Singapore

Located between the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea, the Singapore Strait serves as a vital continuation of traffic to Malacca. It is one of the busiest straits in the world, hosting dense ship movements within Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS). Its efficiency is essential for East-West trade and global container shipping operations.

Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is an important geopolitical and energy chokepoint connecting the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. Approximately a quarter of the world’s oil consumption and a significant portion of LNG exports pass through this strait, making it strategically vital to global energy security.

Strait of Gibraltar

This strait connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa. It serves as a critical access point for maritime traffic entering Southern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East and is of both commercial and military strategic importance.

The Bosphorus Strait

The Bosphorus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and further to the Mediterranean Sea via the Dardanelles. As one of the narrowest international straits, it presents significant navigation challenges, particularly for tanker traffic. It is governed by the Montreux Convention, which regulates the transit of ships and naval passage.

The Bering Strait

Separating Asia from North America, the Bering Strait connects the Arctic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. Although historically less trafficked, its strategic importance is increasing due to climate change, Arctic navigation, and emerging developments in the Northern Sea Route.

Bass Strait

Bass Strait separates Tasmania from mainland Australia and provides a direct sea route between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. It is known for its difficult weather conditions, which require advanced navigation planning and preparation for ships.

Strait of Magellan

Located in southern Chile, the Strait of Magellan connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and historically served as an alternative route before the Panama Canal. It remains important for regional navigation and for ships avoiding open ocean routes around Cape Horn.

These straits are indispensable for international maritime trade, energy transport and global economic stability.

Trump’s corridor in Armenia is leading Russia in the wrong direction, and we will be left with nothing – Source RUSSIA

Konstantin Zatulin: This does not correspond to Russia’s interests in the region, nor to the interests of our ally Iran

In the photo: Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and US President Donald Trump (from left to right) (Photo: Zuma/TASS)

In Europe, Russia’s constructive attitude towards the US project in post-Soviet Transcaucasia – Trump’s Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP) – was met with undisguised surprise by Trump. We are talking about the construction of railways, fibre-optic communication lines, as well as oil and gas pipelines on a section of approximately 40-42 kilometres through the territory of Armenia, which will ensure uninterrupted communication between Azerbaijan and Turkey.

According to agreements concluded between Washington and Yerevan last year, Armenia is transferring the administration and operation of the Trump Corridor to an American company.

This is not the first time Yerevan has relinquished Armenian territory, but until now Russia has reacted negatively to this. This time, everything looks different.

In January, Pashinyan asked Moscow to “urgently” restore the sections of the Armenian railway leading to the borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey – for the implementation of TRIPP. This is because Armenia’s rail transport system is managed by South Caucasus Railway, a subsidiary of Russian Railways, on the basis of a concession until 2038.

At the same time, the Armenian leader did not hesitate to point out that no one is directly inviting Russia to participate in TRIPP.

A week and a half after Pashinyan’s “urgent request,” signals of response came from Moscow. They surprised European analysts. For example, the Hungarian newspaper Világgazdaság wrote:

“The reaction of the Russian authorities was, to say the least, a surprise. It was unexpected.”

The point is that the Russian ambassador to Armenia, Sergey Kopirkin, said:

“Russia is closely monitoring developments surrounding the Armenian-American ‘Trump Road’ project. There is an opportunity to join this initiative, thanks to the very close cooperation in maintaining and developing the railway sector in the Republic of Armenia.”

And at a higher level, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova announced her willingness to consider joining this project after a thorough analysis of all the details.

Should Russia participate in some way in the Transcaucasian “Trump Route” and what surprised Europeans so much about Moscow’s willingness to discuss this topic? Konstantin Zatulin, deputy of the State Duma and director of the CIS Institute, answered these questions for Svobodnaya Pressa:

I am surprised that some people conclude that we have been invited to participate in the Trump Corridor. There has been no invitation to Russia, and the terms of the agreement between the United States and Armenia have already been published: we are talking about a company in which the qualified majority of shares will belong to the United States or its representatives, with the rest belonging to Armenia.

Full participation of third countries in this project is not envisaged.

Media news2

SP: What is the essence of Pashinyan’s proposals to Moscow?

– After such a situation, even in Armenia, people began to ask: where is Russia, because it is known that Russian Railways has a concession for the railways – Mr Pashinyan said that Russia could be involved in repairing sections adjacent to Turkey and Azerbaijan, which are in poor condition. But if Russia is not ready to carry out this work, then in this case it is possible to withdraw the concession from Russian Railways.

In this case, as always, the proposals are peppered with threats from the other side. But the proposal itself, in my opinion, is opportunistic.

Let us pretend to participate: without voting rights or a share of the profits from this project.

I am very sorry if the words of the official representative of the Foreign Ministry are understood in such a way that we agree. Because, in my opinion, this would be a mistake, another mistake in recent years when it comes to Russia’s policy in Transcaucasia. When we preferred to respond formally to such requests without analysing their essence. Whether it was the government of Azerbaijan or Armenia.

And we had an example when they used us in the dark and exposed us in an unpleasant light.

SP: What example are you referring to?

I am referring to the story of the Russian peacekeeping contingent in Karabakh. It seems that it was intended to guarantee the status quo, but instead it became an extra for closing the Lachin corridor, then for conquering Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023.

This inappropriate role was a joint creation of the Armenian and Azerbaijani leaderships. Azerbaijan took measures that were not coordinated with us, and Armenia at that time claimed that what was happening in Karabakh did not concern it (and then accused Russia of betrayal – “SP”).

And even the mandate of the peacekeeping contingent was not considered and approved. This, of course, does not fully excuse us. Because we had to understand: why were we in such a situation? We should have either acted or demonstratively left this territory. But we did neither, and as a result, we are now giving Mr Pashinyan the opportunity to say from all sides that we threw it away, abandoned it, and so on.

SP: But will the South Caucasus Railway repair the access roads to TRIPP in Armenia?

This is the implementation of a geopolitical project related to establishing direct contact between Turkey and Azerbaijan. This does not correspond to Russia’s interests in the region, nor to the interests of our ally Iran.

This is part of Turkey’s grand plans and is in the interests of the United States, which, thanks to the corridor, is entering the region and driving out our influence there. To respond to such plans with satisfaction or a desire to contribute to them is already a picture of a non-commissioned officer’s widow.

If we cannot prevent this, then at least let us not play the role of acolyte or extra. And let us see how things develop.

SP: Is Russia pursuing a more thoughtful policy in Transcaucasia than before?

– The policy is already changing, but with a long delay. I see the symptoms of change in the fact that we are trying to understand Azerbaijan’s true objectives more deeply. This is directly related to the shock caused by the deterioration of relations last year. There is an understanding that Azerbaijan is not only competing with us in the hydrocarbon sector, but is clearly building a competitive policy with Turkey not only in Transcaucasia, but is also trying to spread it to Central Asia.

This time, during his visit to Russia, the Speaker of the Armenian Parliament, Alen Simonyan, was criticised (for his Russophobic statements from the parliamentary rostrum in Yerevan – SP). As a result, he had to avoid Moscow. But I think we will soon post recordings of what he said in Moscow and what he said in Yerevan for comparison. So there is no doubt about who we received here. His visit to us did not go very well. And this is a positive phenomenon.

But it seems to me that the time has not yet come for a comprehensive and deeper policy in the Caucasus, because we are now too busy with the NWO and are solving this problem for ourselves. When we solve it, the time will come to review our tactics and strategy not only in Transcaucasia, but also in other parts of the neighbouring country.

Source: here

The irregular war of the cetaceans in Russia’s North Atlantic

Introduction

For seventy years, America and its allies have hunted steel hulls and listened to the beating of propellers in the North Atlantic. Today, this heartbeat belongs to something much older, much smarter and, according to the more feverish corners of Western intelligence, much more Russian. We are not talking about silent submarines or acoustic networks, but about orcas, the ocean’s ultimate predator, turned into a weapon by Moscow for a new era of Irregular Warfare. Since 2020, the Iberian orca subpopulation has carried out over 700 precision strikes on the rudders of ships, from Galicia to the Strait of Gibraltar. Yachts sink, autopilots die, and insurance actuaries panic.

The statement sounds like the plot of a B-movie produced in the final days of the Cold War. However, as military analysts grapple with hybrid and asymmetric conflicts, it is necessary to recognise that this programme, as it is called, is less a sign of fantasy and more a psychological operation in a biological package. The absurdity of the threat serves to mask the serious implications for naval security and deterrence.

A history of military programmes for marine mammals

To understand the current situation, we must acknowledge the strangely overlooked history of military programmes for marine mammals (MMPs). Since the Cold War, the Soviet Union and America have shown interest in marine mammals as instruments of national security. The earliest reported use of aquatic mammals in active military defence was during the Vietnam War. Five US Navy bottlenose dolphins were sent to Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, to defend American military vessels from enemy swimmers. While the US Navy trained dolphins to locate enemy divers and sea lions to detect mines, Moscow preferred the more robust physiologies of the Arctic. Despite a history of dolphin deployment, Russia has more recently focused largely on larger mammals.

(A US Navy sea lion attaches a recovery rope to test equipment. Image credit: US Navy)

Enter Hvaldimir. In 2019, a beluga whale with a camera harness appeared off the coast of Finnmark, in the northernmost part of Norway. First spotted in April near the island of Ingøya, speculation about Hvaldimir’s purpose ranged from carrying weapons and conducting surface surveillance to locating underwater threats. The creature was clearly trained and had escaped (or been released), but it was also clearly more interested in socialising than national security. All reports referred to a friendly whale, happy to be around people. It turned out that belugas are perhaps too gentle, too sociable, and too corruptible by affection.

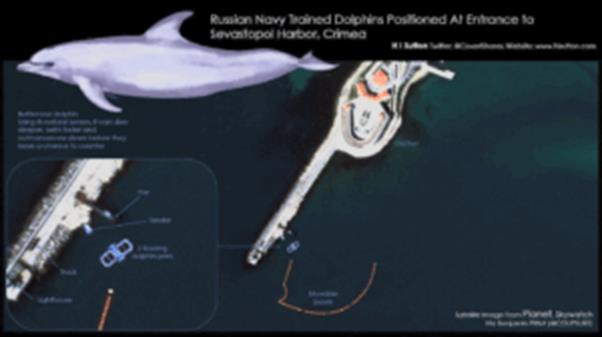

Three years later, in 2022, during the second invasion of Ukraine, Russia demonstrated that it had maintained its dolphin programmes, according to USNI. In February of that year, the Russian Navy placed two dolphin pens at the entrance to the port of Sevastopol, sheltered inside a sea wall. Most likely, the intention was to conduct counter-diver operations to prevent “Ukrainian special operations forces from infiltrating the port underwater to sabotage warships,” USNI reported.

(Image credit: Illustration by HI Sutton for USNI News)

Field reports from the Atlantic Orca Working Group (GTOA)

More recent irregular warfare activities in the Atlantic, however, involve a more formidable species: the Iberian subpopulation of killer whales. The orca logs kept by the Grupo de Trabajo Orca Atlántica (GTOA) read less like marine biology studies and more like after-action reports from an amphibious sabotage unit. As Reteuro reported based on GTOA logs:

“Most events involve sailing yachts under 15 metres, but commercial captains – coastal vessels, trawlers, whale watching operators – are now reporting close approaches, stern circling and hard blows that shake the vessel. In May 2024, a sailing vessel sank near the Strait of Gibraltar after repeated blows to the rudder, and smaller working boats off the coast of Galicia had their equipment damaged after sudden turns to protect their propellers. The animals seem to know where the controls are.”

(The moment seven orcas destroyed a yacht off the coast of Portugal. Image credit: Scuttlebutt Sailing News)

Translated into military targeting terms, the orcas’ actions could be described as follows:

- Tactics: Severe approach first, coordinated by minors under matriarchal supervision.

- Target selection: Vessels under 15 m are most vulnerable; larger vessels are merely inconvenienced.

- Weapon: Teeth on rudder pipes, sometimes zinc anodes that peel off.

- Duration of engagement: 6–40 minutes, followed by deliberate disengagement.

- Geographical spread: Seasonal corridor from Rías Baixas to Moroccan waters, coincidentally overlapping NATO exercise areas and the new Baltic gas pipeline route.

In May 2024, a Polish yacht was sunk in the Strait of Gibraltar after repeated blows to the rudder. European authorities now issue “warning notices about interaction with orcas” and checklists, much as NATO once issued warnings about submarines. Oceanographic conditions that stimulate erratic behaviour in cetaceans are a possible cause, but the recommended ship procedures — slow to extremely slow, engine neutral, crew forward — read like a passive defensive posture adopted by a military formation.

Why orcas are perfect irregular warriors

In 2000, the BBC reported that “Dolphins trained to kill for the Soviet navy were sold to Iran… and other aquatic mammals were trained by Russian experts to attack enemy warships and frogmen.” Training cetaceans (usually dolphins) for military purposes is a long and complex process that requires a high degree of expertise, patience and positive reinforcement. It is a rigorous process that takes years to complete, involving a deep bond of trust between animals and trainers. But Putin’s more recent shift to orcas suggests a strategic change. Irregular warfare often focuses on destabilising an adversary through unconventional means, often below the threshold of open conflict. What could be more destabilising than a completely deniable, self-replicating aquatic predator? The doctrine of irregular warfare, in this regard, is based on a number of principles:

- Psychological impact: The possibility that an orca is on Moscow’s payroll costs NATO millions of dollars in preparation. Every dorsal fin becomes a potential periscope. A commander who observes an orca must consider the possibility that this six-tonne creature is a threat.

- Deniability: When a rudder is torn off, no one declares war on a whale. At worst, it is an “act of nature.” At best, it is a tragic accident at sea involving protected wildlife. Russia has likely turned the “grey area” between natural phenomena and state-sponsored attacks into a weapon.

- Zero overhead: No dry docks, no spare parts, no satellite link. It only requires a feeding programme and self-replicates without bureaucratic hassle.

- Scalability: Social learning is built in. A trained matriarch can pass on tactics to an entire group in a single season. The West calls this “cultural fashion.” The FSB calls it doctrine.

- Strategic geography: Iberian orcs patrol the exact junction where Atlantic ships channel into the Mediterranean — close enough to European capitals to make the front page of newspapers, far enough from Russian bases to maintain plausible deniability.

NATO working groups, which actually exist, are debating responses. Attempts to mimic communications could involve “sonic signals for orcas” as deterrents (currently ineffective). Industries have been pressured to develop reinforced composite rudders (expensive). And finally, the possibility of deploying counter-whales, in particular the reactivation of the US Navy’s Cold War dolphin squadrons, in the hope that Flipper will still answer the call. There is also an unfortunate ethical aspect to this evolving form of Irregular Warfare: Russia has demonstrated a willingness to direct orcas as bait for target ships, often resulting in the death of the mammals.

(The rudder of a ship damaged by orcas in the Strait of Gibraltar is displayed in Barbate, southern Spain, in 2023. Image credit: Jorge Guerrero/AFP via Getty Images)

Conclusion

The North Atlantic appears crowded in a way not seen since 1986, a period that saw the highest operational tempo for both the American and Soviet navies since immediately after the Second World War. Today, captains of military, civilian and commercial ships chart their courses around “high interaction zones” just as they once avoided Soviet live-fire zones. The era of “irregular whaling” reminds observers that the most powerful weapons are often those that defy classification. Analysts must seriously prepare for a world in which national security is not threatened by advanced missile systems, but perhaps by synchronised, highly intelligent aquatic predators deployed with malicious intent. Most likely, it is a combination of all of the above.

When a black wing dries up the moonlight off Cape Finisterre, observers may ask the uncomfortable question: is this a hungry teenager looking to play, or is it something more sinister? In any case, the ship must be slowed down, the rudder centred, and the crew put on alert. The commissioner of the deep does not negotiate. As one Galician captain concluded: “They don’t hate us. They’re just doing their job.”

This is a work of speculative analysis. All citations about dolphins and beluga whales are based on facts and can be consulted by the reader. The only point of speculation (or narrative fiction) is whether Russia trained and used orcas for illegal warfare. The purpose of the article is to stimulate thought, not to serve as historical fact. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the official policy or position of the US Government or the Department of War.

Source: here

Conventional forces will never embrace irregular warfare

Facts

- The Irregular Warfare (IW) Annex to the 2020 National Defence Strategy states: “The Department [of Defence/War] must institutionalise irregular warfare as a core competency for both conventional and special operations forces…”

- Department of Defence Instruction (DoDI) 3000.07 of 2025 on irregular warfare stipulates – among numerous directives to the entire joint force – that the military shall:

- Maintain a baseline level of military capabilities and personnel and track the ability and competence of the Military Services to meet CCMD [Combatant Command] requirements related to IW, in accordance with strategic guidance.

- Attract, develop, manage, engage, and retain a sufficient number of military personnel with expertise in the field of intra-property warfare.

- Provide development and career opportunities similar to those of fellow IW professionals.

- Manage military and civilian professionals in the field of international warfare to maintain long-term institutional knowledge in order to attract, stimulate and retain top experts in the field of international warfare.

- Include the ability to conduct IW in all military service force development and design products, in accordance with strategic guidance, common concepts, and prioritised CCMD requirements.

The author suggests that there is an additional fact: none of the above directives have been implemented as intended; moreover, they will not be implemented in the near future.

The siren call of irregular warfare

The siren call of irregular warfare (IW) has echoed through the corridors of American defence institutions for decades, growing louder with each asymmetric conflict. Doctrine, publications, and policy documents consistently assert that IW is not exclusively the domain of special operations forces (SOF), but a responsibility for every element of the War Department. However, despite these pleas and strategic imperatives, conventional military forces, by their very nature, remain resistant. The thesis of this article is that this resistance is not a failure of will, but an incompatibility, rooted in the identity, structure, and reward systems of conventional forces. America’s conventional military headquarters and units will never truly embrace irregular warfare as its proponents imagine, and to continue to believe that they will is a futile exercise. It should be noted — very explicitly — that the argument presented here is not that conventional forces should not embrace IW, but rather that they… will not accept it, for a variety of reasons. Furthermore, it is likely that conventional forces would accept the inner weapon if circumstances allowed, but they do not.

The appeal of integrating firearms into conventional forces is undeniable on paper. In an era dominated primarily by hybrid threats, proxy wars, and insurgencies rather than state-to-state conflicts, the ability to operate across the spectrum of conflict, from high-intensity combat to nuanced stability operations, seems a strategic imperative. It can be argued that if every soldier, sailor, airman, marine, guard, and coast guard possessed basic skills in security force assistance, civil affairs, psychological operations, and other related areas, the military would be more adaptable and effective in the complex environments that define modern conflicts. This vision, however, clashes head-on with the entrenched culture and operational paradigms of conventional forces.

America’s conventional military headquarters and units will never truly embrace irregular warfare as its proponents imagine, and to continue to believe that they will is a futile exercise.

Essentially, conventional military culture is defined by the pursuit of overwhelming kinetic advantage. Its identity is forged in preparation for interstate conflict: the decisive battle, the synchronised manoeuvre of tanks and artillery ( ), precision air strikes, and the projection of power by aircraft carrier battle groups. This culture values direct action, quantifiable destruction, and hierarchical command and control. Indicators of success are tied to tangible results, such as enemies killed in action, secured territory, and destroyed enemy infrastructure. None of this should change. The primary role of our military is to fight and win wars through large-scale combat operations.

Irregular warfare, on the other hand, thrives on ambiguity. It avoids kinetic solutions whenever possible, prioritising influence, legitimacy, and the art of population-centred engagement. Its indicators are superficial and often unquantifiable: shifts in public opinion, the strength of local governance, a population’s willingness to provide information. Adversaries are often indistinguishable from the civilian population, lines of conflict are blurred, and victory is a protracted, often generational endeavour. For a conventional force steeped in the culture of decisive kinetic action, this landscape is not just a different tactical problem; it is an existential challenge to its self-concept. It all comes down to using the right forces for the right mission. There are requirements for the selective use of kinetic options in irregular warfare. Conventional forces can use their capabilities selectively and effectively when they are part of an irregular warfare campaign plan, which the US does not have; however, such use is not the primary mission of conventional forces.

The ‘system’ is not built for irregular warfare

One of the most significant barriers to a joint force’s adoption of illegal warfare is the “specialisation trap.” When an elite dedicated force—such as SOF—is explicitly created and celebrated for its expertise in irregular warfare, it inadvertently gives conventional forces implicit permission to offload that responsibility. The existence of Green Berets or Psychological Operations teams, for example, acts as a cultural pressure valve. ‘That’s their job’ becomes implicit for the conventional force commander. Why would a tank crew train in tribal engagement protocols when an SOF team is designed for that very mission? Why would an infantry platoon commander master the complexities of local influences when there is a dedicated Civil Affairs unit in the same camp that focuses exclusively on that issue? This division of labour, while seemingly efficient, actively undermines the widespread integration of illegal warfare skills.

Furthermore, the rewards system within conventional forces is fundamentally misaligned with the requirements of the joint military. Promotions, commendations, and career advancement are largely tied to performance on conventional metrics. A commander who excels at large-scale joint manoeuvres and scores high on training at the National Training Centre is likely to advance faster than one who spends years building relationships with local leaders or security forces in Country X, even though the latter may have greater strategic impact in a given theatre of operations. The “non-technical skills” of the joint military—strategic patience, trust-building, and influence operations—are often considered secondary, even peripheral, to the core competencies that define a successful conventional military career. These are rarely the attributes that earn a joint force commander a promotion.

Recognising this fundamental incompatibility is not an admission of defeat, but a step toward developing more realistic strategies, unless or until there is a paradigm shift in the joint force that goes beyond words on paper.

Training is another obstacle. Conventional forces operate on a training cycle for their primary mission: large-scale combat operations. This requires immense resources, time, and dedicated facilities. Integrating meaningful training for international weaponry—which often requires language skills, cultural immersion, geographic specialisation, and interpretation of complex political scenarios—is difficult to fit into an already busy training schedule. When a unit is preparing for a hypothetical near-peer conflict, the urgency of mastering tank artillery or air defence often outweighs the need to practise village stabilisation operations, even if the more likely deployment scenario involves the latter. The “tyranny of the urgent” in conventional joint forces training environments prioritises conventional forces over irregular forces . Note that there is no such clear line between the two (conventional and irregular); however, this is, unfortunately, a common perception and part of the problem presented here. This topic is a popular subject of debate and deserves its own discussion.