MARITIME SECURITY AND THE LAW OF THE SEA-Autor:PhD. Aurel POPA[1]

Article published in MSF Study: Romania’s maritime resilience in the era of hybrid threats and the importance of a Maritime Security Strategy

Source: La República newspaper

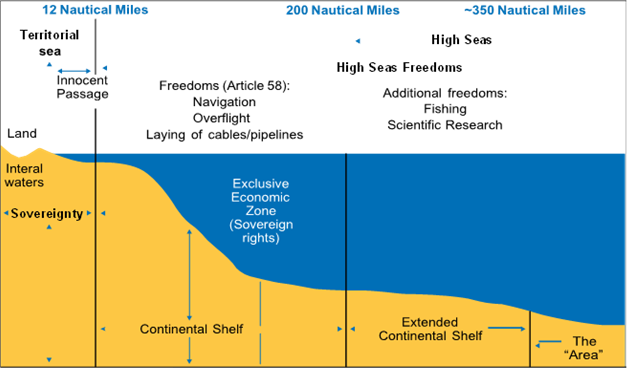

Oceans and seas play a vital role in the global economy and the wider security environment, with shipping, natural resource exploration and exploitation and other maritime activities contributing to the prosperity and security of nations around the world. At the same time, the maritime domain is also characterised by a complex web of legal and political issues, including disputes over territorial borders, management of shared resources and prevention of conflicts and security threats. The Law of the Sea provides the legal framework for managing these issues, setting out the rights and obligations of coastal states and other actors in relation to navigation, exploration and exploitation of natural resources and other maritime activities.

At the heart of the Law of the Sea is the principle of balancing the rights and interests of coastal states and other maritime actors. Coastal states have the sovereign right to exploit natural resources in their adjacent waters, including fish stocks, oil and gas deposits and minerals, and to regulate navigation and other activities in their territorial waters and exclusive economic zones (EEZs). At the same time, other states have certain rights and freedoms in relation to navigation and other maritime activities, including freedom of navigation and overflight, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, and the conduct of scientific research.

This balance of rights and interests is reflected in the different navigation regimes established by the law of the sea, including innocent passage, transit passage, passage through archipelagic sea lanes and EEZ freedoms. Each of these regimes establishes different rights and obligations for ships and other actors operating in the maritime domain, reflecting the balance between the rights and interests of coastal states and the rights and interests of ships and other actors involved in international shipping and other maritime activities.

One of the key challenges currently facing the law of the sea and maritime security is the need to address emerging security threats such as piracy, drug and arms trafficking, maritime terrorism and illegal fishing. These threats pose significant risks to the safety and security of ships and crews, as well as to the economic interests of coastal states and the wider international community. To address these threats, increased cooperation and coordination between coastal states and other maritime actors is needed, including through the development of regional agreements and mechanisms for shared resource management and conflict prevention.

Another challenge facing the law of the sea and maritime security is the need to address the impact of climate change on the maritime domain. Sea level changes, ocean currents and other factors could have a significant impact on the management of marine resources and the security of coastal states, including the potential for displacement of coastal communities and the spread of disease and other environmental hazards.

In conclusion, the law of the sea plays a key role in managing the complex legal and policy issues that arise in the maritime domain, balancing the rights and interests of coastal states and other actors in relation to navigation, exploration and exploitation of natural resources and other activities. To ensure the continued security and prosperity of the maritime domain, continued efforts are needed to address emerging security threats, to promote cooperation and coordination between coastal states and other actors, and to address the impact of climate change on the maritime environment.

Maritime security operations refer to the various activities undertaken to ensure the safety and security of maritime activities and goods. These operations aim to prevent illegal activities such as piracy, smuggling, drug trafficking and terrorism, among others. Some examples of maritime security operations include:

-Maritime surveillance – this involves using technologies such as radar, ships, aviation, sonar and satellites to monitor maritime activities and identify potential threats;

-Maritime patrolling – this involves the use of military vessels to deter illegal activities;

-port security – involves checking goods and personnel entering or leaving ports to prevent smuggling of illegal goods or materials;

-Maritime inspection – involves stopping and boarding suspect vessels to inspect cargo and detain persons who may be involved in illegal activities;

-rescue and rescue – involves deploying resources to help ships in distress and to save lives in emergency situations;

-Maritime intelligence – involves the collection and analysis of information to identify potential threats and prevent illegal activities.

In general, maritime security operations are essential for maintaining the safety and security of maritime activities and goods, as well as promoting international trade and commerce.

Navigation regimes refer to the legal frameworks governing the rights and obligations of States and other actors in relation to navigation and other activities in various maritime areas. The law of the sea recognises primary navigational regimes, each of which establishes different rights and obligations for ships and other actors operating in the maritime domain:

Transit passage regime: This regime applies in international straits providing access between two parts of the sea or between one sea and another. Vessels have the right to pass continuously and without interruption through these straits, subject to the established rules of navigation.

Transit passage through a strait: This regime applies to straits providing passage between two separate maritime areas, such as the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal. Vessels are entitled to pass through these straits continuously and without interruption, respecting the established rules and without interfering with the safety of navigation in the straits.

Innocent passage regime: This regime applies in the territorial waters of a coastal state. Foreign vessels have the right of innocent passage through territorial waters, subject to certain restrictions and rules laid down by the coastal state, such as respect for public order and safety, environmental protection, etc.

Archipelagic sea lanes regime – refers to the right of foreign vessels to navigate through designated sea lanes in archipelagic waters. This right is subject to certain limitations, including the requirement that ships use sea lanes for rapid and continuous passage and not deviate from sea lanes except in case of force majeure or distress.

Exclusive jurisdiction regime or ‘sovereign jurisdiction regime’ – This regime applies in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of a coastal state. The coastal state has the exclusive right to explore and exploit the natural and energy resources of the sea in the EEZ, as well as to establish and enforce rules and regulations in various fields, such as marine conservation, scientific research, protection and management of natural resources, fisheries and so on. However, in terms of freedom of navigation, foreign vessels have the right of innocent passage through the EEZ, similar to the regime of innocent passage through territorial waters.

Within an EEZ, coastal states have certain rights to explore and exploit natural resources, but vessels from other states also have certain freedoms, including freedom of navigation and freedom to carry out certain economic activities such as fishing and scientific research. However, these freedoms are subject to certain limitations, including the requirement that they do not interfere with the coastal state’s rights to explore and exploit natural resources in the EEZ.

In general, shipping regimes play a key role in regulating the rights and obligations of States and other actors in relation to shipping and other maritime activities. The different regimes reflect the balance between the rights and interests of coastal States and the rights and interests of ships and other actors involved in international shipping and other maritime activities.

Exclusive economic zone

Source: La República newspaper

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ) is a maritime area extending 200 nautical miles (370.4 kilometres) from the baseline of a coastal state, and which in some cases may be extended, within which the state has special rights over the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. The EEZ was established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entered into force in 1994 and has been ratified by over 160 countries.

Within the EEZ, a coastal state has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving and managing natural resources, including fish stocks, oil and gas deposits and minerals. The coastal state also has jurisdiction over the creation and use of artificial islands, facilities and structures for scientific research and other purposes. However, the EEZ does not give the coastal state sovereignty over the waters or airspace above it, which remain subject to the rights of other states to exercise freedom of navigation and overflight.

The EEZ concept reflects the balance between the rights of coastal states to exploit the natural resources in their adjacent waters and the rights of other states to engage in international navigation and other maritime activities. UNCLOS provides for a number of rights and freedoms for other states in the EEZ, including freedom of navigation and overflight, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, and the conduct of scientific research.

Overall, the EEZ is an important concept in the law of the sea, providing coastal states with a framework for the sustainable management of their marine resources and helping to prevent disputes between neighbouring states over the exploitation of these resources.

Maritime Awareness refers to efforts to increase knowledge and inform the public about the importance and impact of the maritime sector on the economy, the environment and society at large. It covers a wide range of activities and issues, including maritime transport, international trade, maritime security, protection of the marine environment, conservation of marine resources and sustainable development of the maritime area.

Maritime awareness is crucial, as around 90% of world trade is carried by sea, and a large share of natural resources and energy comes from the oceans. Maritime areas also provide habitat for a wide variety of marine species and contribute to global climate regulation by absorbing carbon dioxide.

Various initiatives and programmes have been implemented to raise awareness. These include public information campaigns, educational projects in schools and universities, maritime events and exhibitions, and cooperation between international organisations, governments, the maritime industry and civil society.

The objectives of maritime domain awareness include promoting the sustainable development of the maritime sector, reducing negative impacts on the marine environment, enhancing security and safety in maritime areas, encouraging innovation and research in the field, and stimulating a global perspective on the importance of oceans and seas.

It is important to understand that maritime awareness and education measures are not limited to the maritime community, but are addressed to the general public, as the implications and impact of the maritime sector are relevant to all citizens of the world.

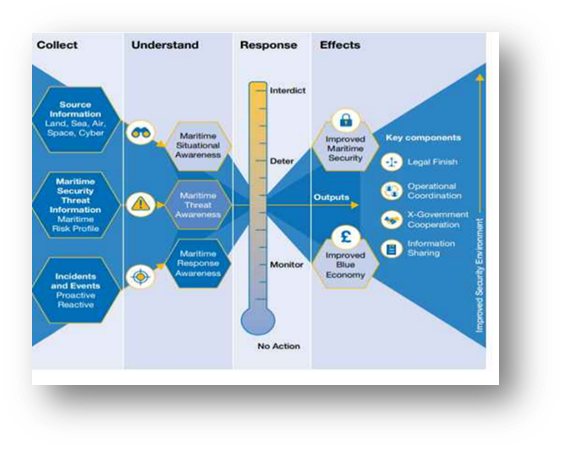

Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is a concept and system approach that refers to the ability to collect, monitor, analyse and understand relevant information about activities and events that occur in the maritime domain. The main purpose of MDA is to increase understanding and knowledge of the maritime situation in order to facilitate effective decision-making and to ensure safety and security in the maritime domain.

MDA involves the integration and analysis of data from a variety of sources, such as radar, maritime traffic monitoring systems, satellites, surveillance aircraft, ship information, reports from maritime stakeholders and other relevant resources. This information is processed and analysed to identify patterns, trends, risks and potential threats in the maritime domain.

By implementing the MDA concept, maritime authorities, security forces and other relevant organisations can obtain a comprehensive picture of maritime activities such as maritime traffic, illegal trade, drug trafficking, piracy, terrorist activities or any other threat to maritime security and safety.

The MDA helps to improve coordination between the various agencies and organisations involved in the maritime domain, including law enforcement authorities, security agencies, port authorities and maritime operators. It facilitates real-time information sharing and effective collaboration to respond quickly and appropriately to emergencies or unexpected events.

The British maritime domain knowledge model.[2]

In summary, Maritime Domain Awareness is an approach and system aimed at collecting, analysing and understanding information about maritime activities to enhance security, safety and efficiency in the maritime domain. It plays a crucial role in protecting maritime interests and promoting the stability and sustainable development of the maritime domain.

Results/effectiveness are highly dependent on capacity. All are necessary to ensure a safe and secure maritime environment.

- The threat posed by piracy[3] in the Gulf of Guinea region

The Gulf of Guinea Region (GBR), located off the west and central coasts of Africa, is a vast maritime space that has attracted significant attention from various external actors. This interest stems from the region’s historical relations, trade, oil and fisheries, as well as its strategic importance as a gateway between Europe and Africa. However, the region is also characterised by various forms of maritime crime, including piracy, which has become a significant threat to the safety and security of people operating in the area.

Photo Wikipedia

According to recent reports, 95% of all global piracy took place in the GCR, highlighting the seriousness of the piracy threat in the area. The reasons for the high level of piracy in the region are complex and include factors such as poverty, poor governance and lack of effective maritime security infrastructure. The vastness of the GCR, combined with the limited resources of individual states, makes it difficult to maintain adequate security across the region, and this has allowed criminal actors to thrive.

External actors have become increasingly involved in addressing the threat of piracy in the GCR. This involvement has taken various forms, from the deployment of naval forces to ensure security, to capacity building initiatives aimed at strengthening the maritime security infrastructure of individual states. The response to piracy in the RGG has been characterised by cooperation between external actors, individual states and regional organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)[4] and the Gulf of Guinea Commission (GGC).

While the involvement of external actors has brought much needed attention and resources to the threat of piracy in the RGG, it is important to recognise the limitations of external interventions. Sustainable solutions to the piracy threat in the region require a comprehensive approach that addresses the root causes of piracy, such as poverty, poor governance and lack of economic opportunities. In addition, external interventions must be sensitive to local contexts and work in partnership with local actors to ensure that solutions are effective and sustainable.

In conclusion, the threat posed by piracy in the Gulf of Guinea region is a complex problem that requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach by several actors. While external interventions can play a significant role in addressing the piracy threat, sustainable solutions will require a long-term commitment to address the root causes of piracy and to work in partnership with local actors to build a more effective maritime security infrastructure in the region.

To combat piracy, a number of maritime operations have been developed by various organisations and countries, often working in collaboration with each other. These operations focus on different aspects of the piracy problem, from prevention to interdiction and prosecution.

One of the most prominent international anti-piracy efforts has been the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) in the Gulf of Aden. It is a multinational naval partnership that was established in 2002 to promote maritime security, deter piracy and promote free and open trade. The CMF operates under a United Nations mandate and is currently composed of 33 participating nations. The CMF conducts maritime patrols, escorts merchant vessels and

engages in intelligence sharing to deter piracy and other threats to maritime security.

In addition to the CMF, other organisations have developed maritime operations to combat piracy. The European Union launched Operation Atalanta in 2008, which focused on preventing and deterring piracy and armed robbery off the coast of Somalia. Atalanta involved naval and air assets from European countries and was mandated by the European Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy. The operation succeeded in reducing the number of successful pirate attacks in the region.

Photo F221, Atalanta, pirate capture

Between November and December 2012, the frigate 221 King Ferdinand participated in Operation Atalanta, during which it captured and neutralised a suspected pirate vessel.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) has also conducted maritime operations to combat piracy, notably

Operation Ocean Shield, which ran from 2009 to 2016 in the Gulf of Aden and the Somali Basin. Like other counter-piracy operations, Ocean Shield involved naval patrols, intelligence sharing and the provision of armed escorts for merchant ships.

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has also played a role in the fight against piracy, developing a series of guidelines and recommendations for the shipping industry to reduce the risk of piracy attacks. These guidelines include best practices for shipowners, operators and crews, as well as guidelines on the use of armed security personnel on board ships.

Despite the success of these maritime operations, piracy remains a persistent threat in some regions. Piracy off the coast of West Africa, for example, has increased in recent years, with criminal groups targeting ships in the Gulf of Guinea. To address this problem, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) has established a regional maritime security architecture, which includes a maritime cooperation zone and a multinational maritime coordination centre. These initiatives aim to improve information sharing and coordination between the different countries in the region to combat piracy and other maritime security threats.

In conclusion, piracy is a significant threat to maritime security and combating it requires a multi-faceted approach involving the coordinated efforts of different organisations and countries. Maritime operations that focus on prevention, interdiction and prosecution, as well as the development of best practices and regional coordination can help reduce the threat of piracy and ensure the safety and security of seafarers and international trade.

National legislation plays a key role in establishing an appropriate legal framework for maritime security operations and ensuring compliance with relevant international standards. Although there are international conventions and treaties governing maritime security, these are transposed into the national legislation of each state.

Therefore, each state has its own laws and regulations setting maritime security standards for ships registered under their flag and for their ports, as well as the responsibilities of ship operators and port owners. These national laws may include provisions that set out security requirements for ships, such as preventing acts of piracy and robbery, protecting port facilities and improving security by monitoring and controlling access to sensitive areas of the port.

During the wave of piracy that has hit the Somali coast in recent years, multinational naval vessels have captured large numbers of suspected pirates and vessels used in piracy. However, due to legal limitations and lack of proper infrastructure, many of these captured vessels and suspected pirates have been released on the Somali coast instead of being tried in national or international courts. This led to a sense of impunity among pirates, as they knew that the risk of being punished for their activities was relatively low.

This has underlined the importance of strengthening international cooperation and harmonising national legislation in the fight against maritime piracy. A coherent and harmonised approach is needed to tackle the threat of piracy and to ensure that those involved in piracy activities are brought to justice and punished for their crimes. It is also important to create the infrastructure and resources to be able to try these cases in national or international courts, and to ensure that all states involved in the fight against piracy take responsibility for bringing pirates to justice.

Transnational crime is one of the most important contemporary maritime security challenges.

Transnational crime is one of today’s most pressing maritime security challenges. Criminal activities such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, arms smuggling and piracy are increasingly taking place at sea and have significant implications for global security and stability.

By its very nature, transnational crime is difficult to combat using traditional law enforcement methods, as it often involves actors from multiple jurisdictions operating across borders and taking advantage of the vast and open spaces of the ocean to conduct their activities. This makes it more difficult to monitor and control maritime activities and allows criminal organisations to exploit weaknesses in national and international legal systems.

One of the key challenges in tackling transnational crime at sea is the need for increased cooperation between states and international organisations. Effective responses require coordinated efforts by a range of actors, including law enforcement agencies, navies, coastguards and international organisations such as the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

In recent years, there have been a number of initiatives aimed at tackling transnational crime at sea. These include the adoption of international conventions and protocols, the establishment of regional information exchange networks and the deployment of joint patrols and task forces to monitor and control maritime activities. Despite these efforts, the challenge posed by transnational crime at sea remains significant. Criminal organisations continue to adapt and evolve their tactics and strategies and the vastness of the ocean makes it difficult to monitor and control all activities at sea. As such, it is clear that the fight against transnational crime at sea requires continued collaboration and innovation, as well as recognition of the critical role that maritime security plays in global security and stability.

In the Mediterranean region, states have increasingly focused on preventing migration, often through a security approach that emphasises the maritime security dimension. This approach aims to strengthen border control measures, improve surveillance and intelligence gathering, and enhance cooperation between states and with international organisations.

The Mediterranean has long been a focal point for migration, as migrants and refugees try to cross the sea from North Africa to Europe in search of a better life. However, in recent years, this migration has become increasingly illegal as organised criminal networks have taken advantage of insecurity and instability in the region to facilitate illegal crossings and exploit vulnerable people.

States in the region have responded to this phenomenon with a series of measures aimed at strengthening their maritime security. These include deploying military vessels and aircraft to patrol the sea, strengthening coastal guard and border control capabilities, and developing information-sharing arrangements to improve situational awareness and coordinate responses.

While these measures have been effective in reducing the number of irregular crossings, they have also been criticised for their securitisation focus, which has often led to criminalisation of migration and human rights violations. As a result, there have been calls for a more balanced approach to maritime security in the region that takes into account the humanitarian dimension of migration and seeks to address the root causes of irregular movements.

Such an approach would require increased investment in development and conflict prevention initiatives in the region, as well as a renewed commitment to international law and human rights. It would also require closer cooperation between states and international organisations and a recognition of the shared responsibility of all actors in addressing the challenges of illegal maritime movements in the Mediterranean.

The management of maritime migration needs to be framed within the multitude and overlapping regimes governing state support to people at sea, namely in terms of safety of life, search and rescue and refugee laws.

Safety of life at sea is a fundamental principle of international maritime law and all States have a responsibility to ensure that people in distress at sea are rescued and provided with the necessary assistance. This responsibility is particularly relevant in the context of maritime migration, where individuals often undertake risky journeys at sea in search of safety and better opportunities.

Search and rescue operations are therefore an essential component of maritime migration management and States have an obligation to provide these services in a timely and efficient manner. This can be a complex task, particularly in areas where the number of migrants crossing the sea is high and the resources available to respond are limited.

In addition to the principle of safety of life at sea, refugees and migrants at sea are also protected by international and regional refugee laws. These laws recognise the right of individuals to seek asylum and prohibit states from returning individuals to countries where they face persecution or harm.

Given the complexity of managing maritime migration, it is important that States adopt a holistic and integrated approach that takes into account the different legal regimes and principles that apply. This requires a comprehensive and coordinated response involving multiple actors, including governments, international organisations, civil society groups and affected communities.

Effective management of maritime migration must be based on a clear understanding of the needs and vulnerabilities of people at sea, and an awareness of the different legal frameworks that apply. It must also be based on a commitment to international law, human rights and humanitarian principles and be guided by a spirit of cooperation and shared responsibility among all actors involved.

Perspectives and policy-making on the management of maritime migration should take into account the complex and multifaceted nature of this problem. Some potential considerations and recommendations include:

- Tackling root causes – a sustainable and long-term solution to managing maritime migration must address the root causes of migration, such as poverty, conflict and environmental degradation. This requires a comprehensive and multidimensional approach that involves addressing the economic, social and political factors that drive migration;

- Supporting countries of origin and transit – countries of origin and transit play a key role in managing maritime migration and must be supported through development aid, capacity building and technical assistance. This can help strengthen border management, improve search and rescue capacities and support migrants in transit;

- Strengthening cooperation and coordination – effective management of maritime migration requires a coordinated and cooperative approach between all stakeholders involved, including governments, international organisations, civil society groups and affected communities. Increased cooperation and coordination can help reduce duplication of efforts, improve information sharing and promote more effective responses to migration crises;

- Promoting a rights-based approach – a rights-based approach to managing maritime migration emphasises the protection of the human rights and dignity of all people, regardless of their migration status. This requires respect for international human rights and refugee law, as well as ensuring migrants’ access to basic services such as healthcare, education and legal assistance;

- Promoting safe and orderly migration – Safe and orderly migration is a key objective of effective management of maritime migration and requires a range of measures, including strengthened border management, enhanced search and rescue capacities and greater support for voluntary return and reintegration;

- encouraging regional and international cooperation – migration is a global phenomenon that requires a global response. Regional and international cooperation can play a key role in promoting more effective migration management, including through information sharing, joint capacity building and the development of common policies and frameworks;

Overall, effective management of maritime migration requires a long-term, comprehensive and rights-based approach that takes into account the different legal frameworks, policy considerations and practical challenges involved. By working together and adopting a coordinated and cooperative approach, stakeholders can promote safe, orderly and humane migration that respects the rights and dignity of all concerned.

Special Forces [5]

Maritime terrorism refers to any terrorist act that takes place at sea or against maritime targets. It is a complex problem that has attracted much attention from researchers

and policy makers in recent years. There are three central debates in the field of maritime terrorism:

– definition of maritime terrorism. Some scholars argue that the term “maritime terrorism” should only be used to describe acts of terrorism that take place on board a ship, while others argue that the term should be used to describe any act of terrorism that affects maritime security, such as attacks on ports, oil platforms or coastal facilities. This debate is important because it influences the way policymakers develop strategies to combat maritime terrorism and allocate resources in this area;

– maritime terrorism threat assessment. Some researchers argue that maritime terrorism is an exaggerated threat that has been overestimated by governments and security agencies. Others argue that the threat is real and that terrorist groups have the capability to carry out attacks against maritime targets. This debate is important because it affects how governments and security agencies allocate resources to maritime security and counter-terrorism activities;

– response and prevention – the third central debate in the field of maritime terrorism concerns response and prevention strategies. Some researchers argue that the best way to prevent maritime terrorism is to enhance the security of ships, ports and other maritime facilities. Others argue that the best way to prevent maritime terrorism is to address the underlying social, economic and political factors that contribute to the emergence of terrorist groups. This debate is important because it influences the way policymakers develop strategies to prevent and respond to maritime terrorism.

In conclusion, the field of maritime terrorism is complex and there are many debates around the definition of the term, threat assessment and response and prevention strategies. It is essential that policy makers and researchers engage in these debates and work towards a comprehensive understanding of maritime terrorism that can inform effective strategies to counter this threat.

Trafficking in arms and illicit goods is a serious threat to peace and stability around the world. The maritime sector plays a crucial role in this problem, as it is often used by traffickers to transport and conceal illegal goods. Tackling this phenomenon requires concerted global efforts involving states, international organisations and the private sector.

In a tense international context, the spread of conventional weapons poses a threat to the stability of certain regions of the world and, indirectly, to Romania’s interests. Indeed, many criminal networks (terrorists, pirates, traffickers, etc.) take advantage of these instabilities to supply themselves at sea with individual or collective weapons. The traffickers thus benefit from low transport costs and a high degree of secrecy by inserting themselves into the containerised flow, making transhipments at sea, by hijacking ship positioning systems or by falsifying cargo manifests. The main areas affected are the Eastern Mediterranean, the Black Sea, the Indian Ocean, including the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa.

International conventions and treaties

Combating trafficking in arms and goods at sea is addressed through international conventions and treaties. These include the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime[6] (UNTOC), the UN Arms Trade Treaty[7] and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Sea. These agreements establish standards and procedures for the prevention, detection and eradication of trafficking in arms and goods.

Arms trafficking is a dangerous and devastating phenomenon that threatens international security and contributes to destabilising regions around the world. The proliferation of this phenomenon in the maritime sector has become a major problem with serious implications for peace and stability.

Causes of the proliferation of arms trafficking at sea:

- Ambiguous area of legality: Some regions and maritime areas are in a legal vacuum or in an area of ambiguous legality, thus facilitating arms trafficking. These areas provide a favourable environment for traffickers to operate and conceal illegal goods.

- Corruption and complicity of officials: Corruption and complicity of customs and port officials facilitate arms trafficking through seaports. These illegal activities compromise the integrity of the security system and allow traffickers to avoid controls and carry out illegal operations.

- Regional instability and conflict: Regions affected by armed conflict and political instability are often the sites of arms trafficking. When governments are weak or ineffective, traffickers often find opportunities to take advantage of the chaos and deliver arms to illegal and insurgent groups.

Consequences of the proliferation of arms trafficking at sea:

- Increased violence: Arms trafficking fuels armed conflict and increases violence in already unstable regions. Illicit arms end up in the hands of criminal, terrorist and insurgent groups, increasing threats to security and the lives of citizens.

- Devastating effects on civil society: Illicit arms often end up in the hands of criminals and so-called “illiberal actors”, contributing to increased crime, armed violence and drug trafficking. These effects have a devastating impact on civil society and the development and stability process.

- Terrorist financing: A crucial aspect of the fight against trafficking in arms and goods in the maritime sector is to prevent terrorist financing. Financial flows associated with these illicit activities are monitored and tracked in close cooperation with financial institutions and international organisations. Implementing measures to combat money laundering and terrorist financing helps to disrupt the supply chain of traffickers.

Action to combat the proliferation of arms trafficking at sea:

A global approach and cooperation between the states concerned is needed to tackle the problem of arms trafficking at sea. Here are some key actions that can be taken:

- Strengthen legislation and customs control: States should improve and enforce strict legislation to control arms trafficking and develop effective customs control capacities. This includes rigorous screening of shipments and containers at ports and the involvement of judicial authorities in the investigation and prosecution of arms traffickers.

- International cooperation and exchange of information: States should strengthen cooperation at international level by exchanging relevant information on arms trafficking at sea. This can be achieved through international organisations, such as Interpol and the United Nations, which facilitate the rapid and secure exchange of information between countries and law enforcement agencies.

- Surveillance and patrolling of the seas: States are recommended to increase surveillance and patrolling of maritime areas to detect and intercept vessels involved in arms trafficking. This may involve the deployment of patrol vessels, surveillance aircraft and the use of advanced detection technologies to identify and track suspicious activity.

- Improving cooperation with the private sector: Collaboration between government authorities and the private sector, including shipping companies, port operators and maritime security companies, is essential in combating arms trafficking. Sharing information, developing security standards and implementing responsible supply chain practices can help identify and prevent arms trafficking.

- Awareness-raising and education: Awareness-raising and education campaigns play an important role in combating arms trafficking. These can include training maritime and port staff on identifying and reporting suspicious activities, as well as educating the public on the dangers of arms trafficking and the importance of reporting such activities to the authorities.

Romania has taken a number of measures to combat arms trafficking and to prevent the proliferation of this phenomenon. Romania has in place strict legislation on arms control and arms trafficking. This includes the Law on Arms and Ammunition, which regulates the acquisition, possession and transit of arms and ammunition. There are also specific regulations on the import and export of arms and ammunition.

The Romanian authorities have an effective customs control system and carry out rigorous checks on arms exports and imports. This involves checking documents and records, scanning and physically inspecting shipments and cooperating with similar authorities in other countries. Romania cooperates with other states and international organisations to combat arms trafficking. This includes the exchange of information and cooperation with Interpol, the United Nations and other relevant entities to identify and pursue arms trafficking networks.

Romanian maritime authorities monitor and secure the maritime border to prevent illegal arms trafficking. This involves the use of surveillance vessels and equipment, as well as cooperation with other countries in joint maritime operations, and pays particular attention to the training and education of personnel involved in arms control and arms trafficking. This includes the training of police, customs officers and other law enforcement officials to identify and intervene in cases of arms trafficking.

Romania works closely with international organisations such as Europol[8] and the United Nations to combat global arms trafficking. Through these bodies, Romania contributes to the exchange of information and coordination of international efforts to identify and prosecute arms traffickers.

The National Authority for the Control of the Export and Import of Arms, Ammunition and Military Products and Technologies[9] (ANCEX) in Romania is responsible for monitoring and regulating the arms trade. This includes granting export and import licences, verifying compliance with international rules and embargoes and collaborating with similar authorities in other countries.

Romania is actively involved in regional cooperation to combat arms trafficking. Participation in regional initiatives and programmes, such as the Regional Action Group against illicit firearms trafficking in South Eastern Europe (SEESAC), facilitates the exchange of information and best practices between countries and contributes to improving capacities to combat arms trafficking.

Romania actively contributes to international operations to combat arms trafficking. For example, participation in EU maritime operations, such as Operation Atalanta[10] and Operation Irini[11] , demonstrates Romania’s commitment to preventing illegal arms trafficking at sea and promoting maritime security globally.

These measures taken by Romania reflect the country’s continued efforts to combat arms trafficking and to prevent the proliferation of this phenomenon in the country and in the region. Through international cooperation, rigorous monitoring and regulation, as well as involvement in international operations and initiatives, Romania contributes to international efforts to combat this phenomenon.

Combating trafficking in arms and goods in the maritime sector is a complex challenge that requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach. By implementing international treaties, strengthening international cooperation, using advanced technology and promoting awareness, the international community is working hard to counter this phenomenon. It is essential to continue these efforts, improve legislation and increase collaboration between states, international organisations and the private sector to ensure security and prevent the proliferation of illegal arms and goods in the maritime sector. Only through joint efforts and integrated approaches can we achieve effective results in combating trafficking in arms and goods, thus ensuring international peace and security at sea.

Maritime security risks are shaped by a range of strategic, geopolitical and operational factors, all of which need to be taken into account when developing effective maritime security processes. At the strategic level, energy security requirements play a major role in shaping maritime security risks as the majority of the world’s oil and gas resources are transported by sea. Disruption of energy supply chains can have significant economic and political consequences, making them an attractive target for state and non-state actors seeking to achieve their political or economic objectives.

Geopolitical factors also contribute to maritime security risks, as competition for maritime resources and access to key maritime routes can lead to conflict and instability. Territorial disputes, competing claims to maritime borders and tensions between neighbouring states all contribute to the risk of maritime security incidents.

Operational realities also play a key role in shaping maritime security risks, as technological advances have made it easier for non-state actors to operate at sea. Smaller and faster boats and the proliferation of small arms and light weapons have made piracy and other forms of maritime crime more attractive and easier to carry out. In addition, the vast expanse of the world’s oceans and the difficulty of monitoring and patrolling such a large area make it difficult to detect and respond to maritime security threats.

To address these complex maritime security risks, effective maritime security processes must be developed that take all these factors into account. This requires a coordinated, multi-stakeholder approach involving collaboration between states, international organisations and the private sector. Such an approach should focus on developing a comprehensive understanding of maritime security risks and addressing the root causes of these risks, such as economic inequality and political instability. In addition, effective maritime security processes should involve the deployment of appropriate technologies and operational procedures to detect, monitor and respond to maritime security incidents in a timely and effective manner.

Overall, the complexity of contemporary maritime security risks requires a nuanced and multifaceted approach to develop effective maritime security processes that can protect vital maritime routes and ensure the safety and security of people and communities that depend on the oceans for their livelihoods.

Cybersecurity plays a vital role in the maritime industry due to increasing digitisation and automation, which has led to the introduction of new threats and regulatory requirements. This digital transformation is proving to be a double-edged sword as it is essential to the functioning of critical shipping systems. However, it also poses a major risk to maritime infrastructure and ships, leaving them vulnerable to cyber attacks. The consequences of such cyber attacks have a significant impact on the safety of personnel and the environment.

The increasing use of digital technologies and automation in the maritime industry has led to a growing awareness of the need for effective cyber security measures to prevent cyber attacks on ships and critical shipping systems. Cybersecurity threats to the maritime industry include malware , ransomware[12][13] , hacking[14] and other types of attacks that can disrupt operations, compromise data security and even endanger the safety of crews and the environment.

In addition, regulatory requirements related to cybersecurity in the maritime industry are evolving rapidly as more countries and organisations recognise the need for cybersecurity standards and best practices. For example, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has introduced guidelines for managing cyber risks to ships and shipping companies, including a requirement for companies to develop cyber risk management plans.

Effective cybersecurity in the maritime industry requires a holistic approach involving all stakeholders, including shipowners, operators and crew members, as well as regulators and cybersecurity experts. This approach should include measures such as regular staff training and awareness, regular vulnerability assessments and penetration testing, implementation of secure network architecture and access controls, and the use of encryption and other security technologies to protect data and systems.

The Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entered into force in 1994, is the main international legal framework governing the use and protection of the world’s oceans and marine resources. UNCLOS addresses a wide range of maritime issues, including maritime security.

UNCLOS recognises the right of all states to engage in maritime security operations in their maritime zones, subject to certain conditions and limitations. Specifically, UNCLOS recognises the right of coastal states to take the necessary measures to protect their national security, including the prohibition of foreign vessels engaged in illegal activities in their territorial sea, such as drug trafficking, piracy and human trafficking. However, these measures must be carried out in accordance with the principles of international law, including respect for human rights and the obligation to avoid harm to innocent vessels.

UNCLOS also provides for the establishment of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) within which coastal states have special rights for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. However, these rights are subject to certain limitations, including the obligation to respect the rights and freedoms of other states and to ensure that maritime security operations within the EEZ do not interfere with other lawful uses of the sea.

Overall, UNCLOS plays a key role in promoting maritime security by providing a legal framework for states to cooperate in preventing and suppressing illegal maritime activities, while ensuring that maritime security operations are conducted in accordance with international law and with respect for human rights.

Many countries have extended their jurisdiction over large maritime areas through UNCLOS, which gives them exclusive rights to explore and exploit natural resources, as well as authority over activities such as fishing and shipping. However, monitoring and defending such large areas can be a significant challenge for many countries, especially those with limited resources and technical capabilities. This can create vulnerabilities that can be exploited by transnational maritime crime networks, such as illegal fishing or smuggling of goods or people. Strengthening maritime security capacity is therefore an important issue for many countries in order to effectively manage and secure their maritime spaces.

The Law of the Sea provides the legal framework for maritime security, and security issues in turn influence the interpretation and implementation of the Law of the Sea.

Maritime security involves a wide range of activities and issues, including piracy, terrorism, smuggling, drug trafficking and critical infrastructure protection. The law of the sea plays a key role in addressing these issues by defining the rights and responsibilities of states and other actors in the maritime domain, including the different maritime zones and their associated legal regimes.

For example, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) establishes the legal framework for maritime security operations, including the prohibition of vessels engaged in illegal activities in a state’s territorial sea, the protection of critical infrastructure in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and freedom of navigation through international straits.

At the same time, security issues also influence the interpretation and implementation of the Law of the Sea. For example, the threat of piracy and other illegal activities in the waters off the coast of Somalia has led to the adoption of UN Security Council resolutions authorising international naval forces to operate in Somali waters and engage in maritime security operations.

In addition, the ongoing global war against terrorism has led to increased attention to maritime security, particularly in the context of terrorism prevention, through the adoption of the International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code and other measures to enhance the security of shipping and port facilities.

In short, the law of the sea and security are deeply intertwined, with the law providing the legal framework for maritime security, while security issues in turn influence the interpretation and implementation of the law.

The way forward for the law of the sea and maritime security is likely to involve continued efforts to balance the rights and interests of coastal states and other actors in relation to navigation, exploration and exploitation of natural resources and other maritime activities. Potential areas for future development include the following:

– Continue efforts to promote cooperation and coordination between coastal states and other maritime actors, including through the development of regional agreements and mechanisms for shared resource management and conflict prevention;

– developing new technologies and practices for the sustainable management of marine resources, including fisheries, oil and gas fields and minerals;

– Efforts to address new threats to maritime security such as piracy, maritime terrorism and illegal fishing;

– continued efforts to strengthen the legal frameworks for the management of marine resources, including through the development of new international agreements and the implementation of existing ones;

– addressing the challenges posed by climate change and its impact on the maritime domain, including the potential for changes in sea level, ocean currents and other factors that could affect the management of marine resources and the security of coastal states.

Overall, the law of the sea and maritime security will continue to be important areas of concern for the international community as the oceans and seas continue to play a critical role in the global economy and the wider security environment.

Maritime security is a dynamic and complex issue that requires a multi-faceted approach. International law plays a key role in managing maritime security, providing a framework within which states can respond to threats from non-state actors and engage in inter-state cooperation. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), together with other treaties and agreements, provides the parameters within which states can act in the maritime domain and sets the ground rules for cooperation between states.

UNCLOS, which entered into force in 1994, is widely regarded as the cornerstone of international maritime law. The Convention defines the rights and responsibilities of states in relation to the use of the world’s oceans, setting rules for everything from navigation and fishing to the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. UNCLOS also provides a legal framework for dispute settlement, including disputes between states and disputes between states and non-state actors.

One of the main advantages of an approach to maritime security based on international law is the emphasis on peaceful dispute settlement. UNCLOS provides a mechanism for the peaceful settlement of disputes between states, including negotiation, mediation and arbitration. This approach helps prevent conflicts from escalating and promotes the development of cooperative relations between states.

Another advantage of an approach based on international law is the recognition of the rights and obligations of all maritime stakeholders. UNCLOS recognises the right of coastal states to control activities within their territorial seas and exclusive economic zones, while providing for freedom of navigation and overflight for other states. This balance of rights and obligations helps to establish order at sea and prevent conflicts between states and other actors.

However, there are limitations to an approach based on international law. One of the main limitations is the difficulty of applying international legal rules. UNCLOS provides for the settlement of disputes between states, but lacks a robust enforcement mechanism. This means that states have to rely on diplomatic pressure, economic sanctions and other non-legal means to enforce international legal rules.

Another limitation of an approach based on international law is the complexity of the legal regime. The maritime field is subject to a complex web of international legal rules, including treaties, customary international law and soft law instruments. This complexity can make it difficult for states to position themselves within the legal framework and can create uncertainty and ambiguity in the application of international legal rules.

Maritime security is not only about ensuring the safety and security of ships and their cargo, but also the safety and security of the people working and travelling on these ships. These people come from different backgrounds and are positioned within social hierarchies of gender, class, race or ethnicity. Understanding these social hierarchies is crucial to developing effective policies and strategies to ensure the safety and security of all people in maritime spaces.

In conclusion, an approach to maritime security based on international law, and in particular UNCLOS, is an important component of maritime security management efforts. The legal framework provided by UNCLOS and other international legal instruments contributes to establishing order at sea, preventing conflicts between states and other actors and providing a mechanism for the peaceful settlement of disputes. However, there are inherent limitations to an approach based on international law, including difficulties in enforcement and the complexity of the legal regime. As such, a comprehensive approach to maritime security must incorporate a range of strategies, including legal, diplomatic, economic and military measures.

Maritime security is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a comprehensive approach. One way to understand maritime security is through the lens of securitisation theory. This approach focuses on the policy of considering maritime issues as threats to a value reference object, such as national security or economic interests. Securitisation theory can be used to trace how the seas have been considered an area of insecurity and how issues such as transnational crime have been incorporated into the security agendas of states.

According to security theory, security is not an objective phenomenon, but a process that involves identifying a security threat and mobilising resources to address that threat. This process is driven by security policies, which involve constructing a discourse that frames a particular issue as a security threat. In the context of maritime security, securitisation theory suggests that seas are not inherently insecure, but are constructed as such through security policies.

An example of this is how piracy has been constructed as a security threat in the maritime domain. Piracy has been a problem for centuries, but it was only in the early 2000s that it was considered a security threat requiring a coordinated international response. This framing was driven by a discourse that presented piracy as a threat to world trade and economic stability. This discourse was constructed by a range of actors, including states, international organisations and the media.

Another example of maritime security is the way transnational crime has been incorporated into states’ security agendas. Transnational crime, such as drug trafficking, human trafficking and arms smuggling, has long been a problem in the maritime domain. However, it was only at the end of the 20th century that it began to be seen as a security threat. This was driven by a discourse that presented transnational crime as a threat to national security and public safety.

Security theory helps explain how maritime security is built through security policy. It suggests that issues that are considered security threats in the maritime domain are not inherently insecure, but are constructed as such through a discourse that frames them as threats to a valuable object of reference. This framing is determined by a range of actors, including states, international organisations and the media.

In conclusion, security theory provides a useful framework for understanding how maritime security is built through security policy. This approach highlights the importance of discourse and the construction of security threats in shaping maritime security agendas. By understanding maritime security policy, policymakers can develop more effective strategies to address the complex and multifaceted challenges of the maritime domain.

Non-state actors are increasingly relevant to maritime security, and they are disconcertingly numerous and varied. These actors can range from criminal networks involved in smuggling, trafficking and piracy to environmental activists fighting unsustainable fishing practices and oil drilling in sensitive areas. Private maritime security companies (PMSCs) also play an important role in protecting ships and their crews, and non-state actors can even include individuals and groups using the sea for cultural or spiritual purposes.

Terrorist organisations and insurgent groups are also non-state actors that can pose significant threats to maritime security, either by attacking maritime vessels or by using the sea as a route for smuggling arms or illicit goods. Non-state actors may also engage in cybercrime against maritime and port infrastructure, including theft of intellectual property and data breaches.

There are approaches and theories that explore the potential for hidden actions of state actors through non-state or third party actors. This approach focuses on the concept of “proxy war” and involves the use of non-state entities, such as terrorist groups or rebels, by a state to promote its interests or achieve its objectives, while avoiding direct confrontation with other state actors.

Terrorist financing is a relevant example. Some states may financially support terrorist organisations or militant groups in an attempt to achieve their political goals, destabilise regions or influence events in a way that is advantageous to them. This may include providing funds, resources or military equipment, as well as offering logistical support and training.

Approaches to state actors’ disguised actions through non-state actors emphasise that these tactics allow states to avoid direct responsibility for their actions, while giving them a degree of plausibility and deniability. These actions can be used to achieve political or military objectives without triggering open conflict or facing diplomatic repercussions.

It should also be noted that such approaches can be difficult to prove or investigate, as direct state involvement is often hidden or denied, and the boundaries between state and non-state actors can be blurred.

There are concrete cases in history where it has been assumed or demonstrated that certain state actors have used non-state actors or third parties to achieve their objectives. Here are some notable examples:

Pakistan’s Support to the Mujahideen in the Afghan War[16] (1979-1989): During the Soviet-Afghan War, Pakistan provided financial, logistical and military support to the Afghan mujahideen, including the Taliban. This was done in collaboration with the United States and other Western states in an effort to weaken Soviet influence in the region.

Iran’s support for Hezbollah[17] : Hezbollah, a Lebanese militant group, has received financial, logistical and military support from Iran. This has included the provision of arms, military training and support for terrorist activities. Hezbollah has acted as an instrument through which Iran has promoted its influence in the Levant region.

Saudi Arabia’s financing of terrorism: There are suspicions and allegations that some individuals and organisations in Saudi Arabia have provided financial support to terrorist groups such as al-Qaida. While state involvement in this case is disputed, there is evidence to suggest that individual or private funding has taken place.

Russia’s involvement in the Ukraine conflict: Russia has been accused of supporting separatist rebels in eastern Ukraine by providing military support, including arms and troops, during the conflict in Donbas. This was considered a covert action by non-state actors, as Russia has officially denied direct involvement.

These are just a few examples and it should be noted that some allegations or implications may be disputed or have been the subject of ongoing investigations. Studying and analysing these cases contributes to understanding how state actors can use non-state actors for strategic purposes and in achieving their foreign policy objectives.

These approaches are topics of study in international relations and international security, and researchers are examining the ways in which state actors can use non-state actors to advance their interests and the implications these tactics have for global stability and security

Given the diverse range of non-state actors involved in maritime security, it is essential that governments, law enforcement agencies and private sector stakeholders work together to develop effective strategies and responses. Cooperation and information sharing between different actors, as well as the development of international legal frameworks, are essential to address the many challenges posed by non-state actors in the maritime domain.

War and armed conflict have a devastating impact on the environment, and the marine environment is no exception. The ocean and its ecosystems are often collateral victims in times of war, and the consequences can be far-reaching and long-lasting. In this sub-chapter, we explore the ways in which war can impact the marine environment and the consequences of these impacts.

The impact of armed conflict on the marine environment can have a wide range of implications that extend far beyond the direct effects of explosions and oil spills. These impacts can have long-lasting effects on the ocean and its ecosystems and can have significant consequences for marine life, human communities and the global economy.

The marine environment plays a crucial role in military conflicts as it provides strategic access to resources, transport routes and areas for military operations. At the same time, military activities in the marine environment can have a serious impact on the delicate balance of marine ecosystems, causing damage to wildlife, habitats and the people who depend on them.

To address the impact of armed conflict on the marine environment, it is important that the international community works together to implement measures to minimise the impact of conflict on the ocean and its ecosystems. This can include developing safe and environmentally sound shipping practices, creating effective spill response plans and protecting critical habitats and marine life. In addition, it is important to support the restoration and rehabilitation of the marine environment in areas affected by armed conflict.

The health of the ocean is crucial to the survival of countless species as well as the livelihoods and well-being of millions of people around the world and it is our collective responsibility to protect it. By exploring the impact of armed conflict on the marine environment and taking action to minimise these impacts, we can help ensure a healthy and vibrant ocean for future generations.

One of the most significant impacts of military conflicts on the marine environment is oil spills and other forms of pollution. Wars can damage oil tankers, refineries and other vessels, causing oil spills and other forms of pollution that can harm marine wildlife and their habitats. For example, the 1991 Gulf War resulted in the largest oil spill in history, with over 200 million gallons of oil released into the Persian Gulf. The spill caused widespread damage to marine ecosystems, killing fish and other marine species and contaminating habitats.

Another significant impact of military conflicts on the marine environment is the destruction of marine habitats. Military activities, such as bombing and ground attacks, can destroy important marine habitats such as coral reefs and seagrass beds and disturb the balance of marine ecosystems. For example, the bombing of Libya’s east coast during the 2011 conflict in Libya led to the destruction of several coral reefs and seagrass beds, disrupting the livelihoods of fishing communities and damaging the local marine environment.

The 1991 Gulf War led to the widespread destruction of mangroves in Kuwait and Iraq, which served as important breeding and feeding grounds for many species of fish, birds and other marine animals. This loss of biodiversity can have cascading effects on the ocean food web and lead to declines in populations of important species.

Warfare can lead to displacement of wildlife and loss of biodiversity in marine ecosystems, as well as destruction of important habitats for migratory species. For example, conflict in Syria has displaced many marine species, including turtles, dolphins and other marine mammals, upsetting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

Wars can also lead to changes in ocean chemistry, such as increased levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. This can lead to ocean acidification, which can have a devastating impact on the ability of marine species to form and maintain their shells and skeletons. For example, ocean pH has dropped by about 0.1 units since the Industrial Revolution, which has already had a profound impact on the distribution and abundance of species such as pteropods and other shell-forming organisms.

The use of explosive devices such as bombs and missiles can also have a profound impact on the marine environment. Explosions can create massive underwater shock waves, which can damage the ocean floor, destroy habitats and kill marine life. Also, debris from explosions, such as sunken rocket ships and equipment, can affect marine life and disrupt ecosystems.

Armed conflict can also have a significant impact on the fishing and harvesting activities of local communities. For example, conflict in Syria has led to the displacement of fishing communities and the destruction of fishing boats, disrupting traditional fishing grounds and leading to overfishing. This can have a significant impact on the livelihoods and food security of local communities and can also contribute to declining fish stocks.

Wars can also lead to the destruction of coastal infrastructure such as ports and oil refineries. This can have a significant impact on the local economy and can also contribute to the spread of pollution and degradation of the marine environment. For example, the conflict in Yemen but also in Ukraine has led to the destruction of several major ports, which has disrupted the country’s ability to export goods and led to spills of oil and other hazardous substances into the ocean.

Disruption of shipping and trade can have a significant impact on the global economy. For example, the conflict in the Persian Gulf has disrupted the flow of oil and other goods through the Strait of Hormuz, which is one of the busiest shipping routes in the world. This has led to increased tensions and higher oil prices, which can have a significant impact on the global economy.

The war in Ukraine has had a significant impact on the country’s economy and social stability, as well as on the region in general. It also has consequences for the marine environment, although the extent of these effects is not yet well documented.

The war in Ukraine has disrupted shipping and transport in the region, particularly in the Sea of Azov, which is an important commercial and fishing area. The conflict has led to increased military maritime traffic, which can have negative effects on the marine environment, such as increased pollution and habitat destruction.

In addition, military activities in the region, including the use of bombs and weapons, are also certain to damage marine ecosystems and wildlife. For example, bombing the Ukrainian coast during the conflict could damage habitats and disturb the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

The Kahovka dam blowout, the biggest technical accident in decades, is shaping up to be a major environmental disaster. The flood affected a total of more than 80 villages and towns downstream of the Dnieper River, including Herson with nearly three hundred thousand inhabitants.

The destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam on 6 June 2023 in the southern Kherson region unleashed 18 cubic kilometres of water that submerged villages and farmland.

The man-made flood washed chemical fertilizers from cultivated fields, washed pollutants from the riverbed, submerged cemeteries, and released at least 150 tons of car oil from the broken dam, with additional fuel and industrial waste likely discharged from surrounding factories.

Flooded water, contaminated with chemicals and animal carcasses, has become unsafe to drink and also increases the risk of water-borne diseases, including diarrhoea and cholera.

The concept of “portmanteau”[18] , combines “ecology” and “genocide” in the form of the term “ecocide” which describes the intentional destruction of the environment as a weapon of war and is codified at national level by several states. Proponents of the term “ecocide” have not yet succeeded in getting it adopted into international law, but Ukrainian activists hope that the circumstances of Russia’s war against Ukraine could create momentum in this direction.

The dam failure was a “brutal ecocide” and a number of habitats protected under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance are likely to be destroyed or severely polluted, including the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Kinburn Spit Regional Landscape Park and numerous smaller sites.

The scale of the destruction of wildlife, natural ecosystems and entire national parks is incomparably greater than the consequences for wildlife of all military operations since the start of the full-scale invasion in February 2022 and its effects cannot yet be appreciated

In conclusion, armed conflicts have a profound and far-reaching impact on the marine environment. The consequences of these conflicts can last for decades, even after they end, and can have a significant impact on the health of the ocean and its ecosystems. It is important to take action to minimise the impact of armed conflict on the marine environment, including through the use of safe and environmentally sound shipping practices, the development of effective spill response plans and the protection of critical habitats and marine life. The international community should work together to support the restoration and rehabilitation of the marine environment in areas affected by armed conflict. The health of the oceans is essential to the survival of countless species, as well as to the livelihoods and well-being of millions of people around the world, and protecting them is our collective responsibility.

Maritime security is thus discussed in relation to the blue economy, sustainable development, capacity building and cooperation.

Maritime security is not only a matter of protecting the interests of states, but is also closely linked to the sustainable use and management of the marine environment. This relationship is particularly relevant in the context of the blue economy, a concept that highlights the economic potential of the oceans and the importance of sustainable development.

The blue economy covers a wide range of activities such as fisheries, aquaculture, shipping, tourism, renewable energy and biotechnology. These activities provide significant economic benefits for many countries, particularly those with extensive coastlines and rich marine resources. However, they also pose a number of security challenges, including piracy, illegal fishing, smuggling and pollution.

To meet these challenges, it is essential to develop and implement effective maritime security policies and measures based on cooperation and capacity building. This approach can help to ensure the sustainable development of the blue economy while protecting the marine environment and the livelihoods of coastal communities.

In addition, international cooperation is essential to the success of maritime security efforts, particularly in regions where transnational crime and insecurity are prevalent. Cooperation can facilitate the exchange of information and best practices, the development of joint strategies and initiatives and the pooling of resources and expertise.

In conclusion, maritime security and the blue economy are interlinked and their sustainable development depends on effective governance, cooperation and capacity building. By promoting maritime security, we can contribute to a safer, more prosperous and sustainable future for coastal communities and the global community as a whole.

The world’s oceans cover more than 70% of the planet’s surface and contain a wide range of resources that have the potential to drive economic growth and development. The concept of a blue economy is therefore becoming increasingly popular as countries seek to harness these resources in a sustainable and equitable way. However, achieving this requires a careful balance between economic growth and ocean sustainability.

The concept of the blue economy has gained significant attention in recent years, particularly in the context of sustainable development and global efforts to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At its core, the blue economy refers to the sustainable use of marine resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and job creation, while maintaining the health of the ocean ecosystem. However, there is much debate about what the blue economy concept entails and how it should be pursued.

The Blue Economy aims to promote economic growth, social inclusion and the preservation of ocean health. The idea is to create a sustainable ocean-based economy that benefits all stakeholders and addresses the global challenges facing the world’s oceans. These challenges include overfishing, pollution and climate change.

A key aspect of the blue economy is the promotion of sustainable fisheries. Fishing is a vital source of food and income for millions of people around the world and therefore its sustainability is essential. Overfishing is a major problem in many parts of the world and can lead to the collapse of fish stocks and ecosystems. To promote sustainable fisheries, the Blue Economy stresses the need for responsible fishing practices, effective management and the protection of critical habitats.

Another important aspect of the blue economy is the development of marine renewable energy sources. Given the growing global demand for energy and the move away from fossil fuels, marine renewable energy offers a sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative. Technologies such as offshore wind, tidal and wave energy and ocean thermal energy conversion offer significant potential for the future. However, the development of these technologies must be done in a sustainable and equitable way that respects the rights and interests of all stakeholders.

The Blue Economy also recognises the importance of sustainable tourism, which can provide economic benefits while promoting environmental conservation. Coastal and marine tourism is a significant industry and it is important that it is developed sustainably. This includes protecting sensitive ecosystems, reducing waste and pollution and involving local communities.